What Will The Next 15 Years Of Power Look Like?

Disclaimer.

This article expresses general analysis for informational and discussion purposes only. The analysis presented is based on publicly available data and forecasts from government agencies and industry sources.

Energy policy, technology costs and regulatory frameworks are subject to change. Readers should conduct independent research and seek professional advice before making business or investment decisions.

This article does not constitute financial, legal, or engineering advice and the views, opinions, thoughts and ideas expressed are those of the author only.

Article Summary.

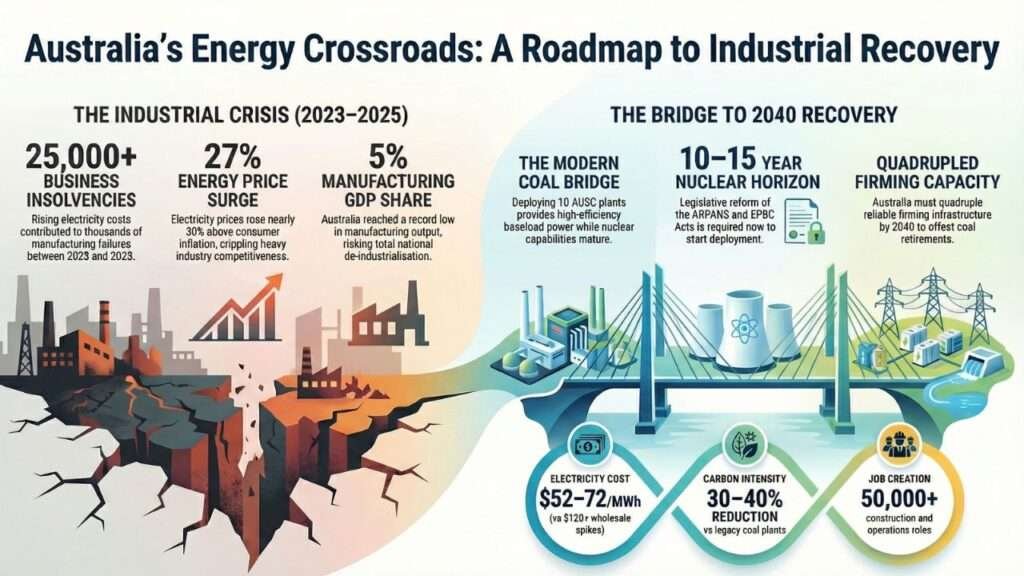

Australia faces a critical 15-year period that will determine whether it rebuilds industrial competitiveness or continues economic decline.

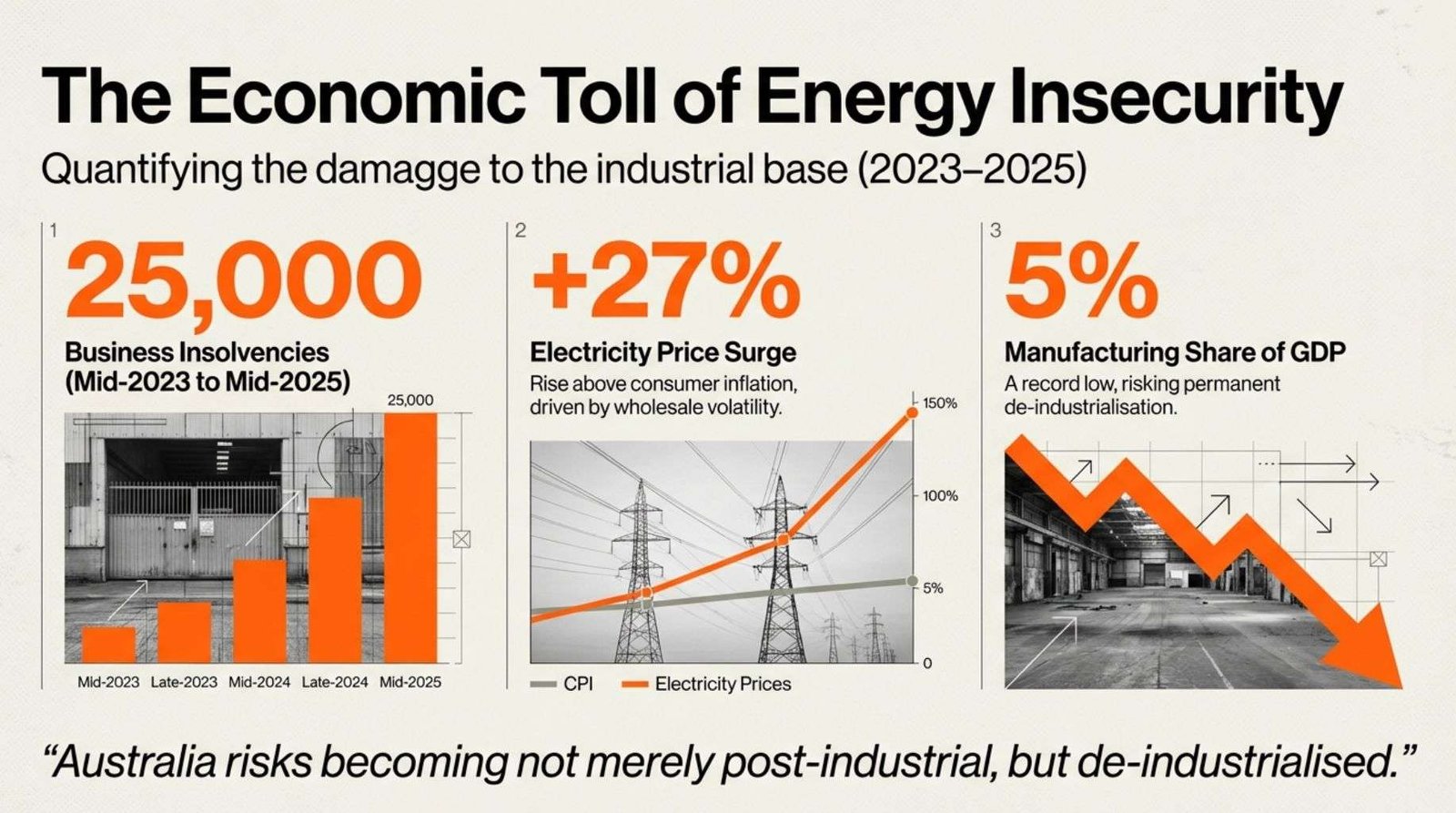

Between mid-2023 and mid-2025, over 25,000 businesses entered insolvency, with electricity prices rising 27% above consumer inflation. Manufacturing’s GDP share dropped to just above 5%, a record low.

Industrial recovery requires stabilising energy prices immediately, strengthening medium-term generation with firm low-emission sources and establishing a credible nuclear pathway.

Without cheap, reliable, round-the-clock electricity, energy-intensive manufacturing, defence production and advanced exports cannot compete globally.

The strategic response involves efficient transitional thermal capacity, quadrupled firming infrastructure by 2040 and a realistic 10-15 year timeline to nuclear deployment.

Top 5 Takeaways.

1. Over 25,000 Australian businesses entered insolvency between mid-2023 and mid-2025, driven partly by electricity prices that surged 27% above consumer inflation.

2. Manufacturing’s GDP share fell to just above 5% by 2025, the lowest on record, risking full de-industrialisation rather than post-industrial transition.

3. AEMO’s 2024 Integrated System Plan identifies that firming capacity must quadruple by 2040 to offset the retirement of 90% of existing coal fleet.

4. Federal legislation (ARPANS Act 1998 and EPBC Act 1999) currently prohibits nuclear power construction, requiring parliamentary amendment plus state-level reforms.

5. Realistic timelines from policy decision to operational nuclear reactor span 10-15 years, meaning delays now extend industrial vulnerability into the 2040s.

Table of Contents.

1. A Nation at an Energy Crossroads.

2. The Case for a Firming Backbone.

3. Bridging to the 2040s: AUSC, HELE and Gas.

4. The Long Road to a Nuclear Option.

5. Building the Institutional Framework.

6. The Legal and Political Roadmap.

7. Integrating Economics and Timelines.

8. Global Lessons in Energy Realism.

9. Why Industry Should Care Now.

10. The Political Imperative.

11. Looking Fifteen Years Ahead.

12. Coal Is The Bridge To Nuclear.

12.1. Reliability Boost.

12.2. Cost Stabilisation.

12.3. Emissions Reductions.

12.4. Industrial and Economic Gains.

12.5. Strategic Bridge to Nuclear.

12.6. Risks and Mitigations.

13. Balance: Industry, Environment, Prosperity & The Cost of Living.

14. Conclusion: Choose Building Over Decline.

15. Bibliography.

1. A Nation at an Energy

Crossroads.

Australia’s recent

economic data reveals significant stress. Over 25,000 businesses entered

insolvency between mid-2023 and mid-2025, as confirmed by the Australian

Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC). For thousands of manufacturers,

rising energy prices contributed to business failure.

Electricity prices surged

approximately 27% above consumer inflation across this two-year period, driven

by wholesale market volatility, network constraints and the global energy shock

that forced domestic gas prices upward.

This shock coincided with

record interest rates and high input costs, creating what some economists now

describe as a “triple threat” to Australian industry.

By 2025, manufacturing’s GDP

share reached a record low of just above 5%. Australia risked becoming not

merely post-industrial, but de-industrialised.

Factories curtailed

operations, smelters reduced output and advanced manufacturing projects shifted

offshore.

Discussions about the

country’s energy future concern the economic foundation of the nation itself.

2. The Case for a Firming

Backbone.

Electricity drives every

segment of industrial growth. For heavy industry, firm, dispatchable baseload

power matters most, generation that runs continuously at predictable cost.

Renewable energy can

provide low-cost kilowatt-hours under favourable conditions, but its

intermittency requires balancing through firming technologies such as pumped

hydro, gas turbine systems, compressed air storage, or nuclear power.

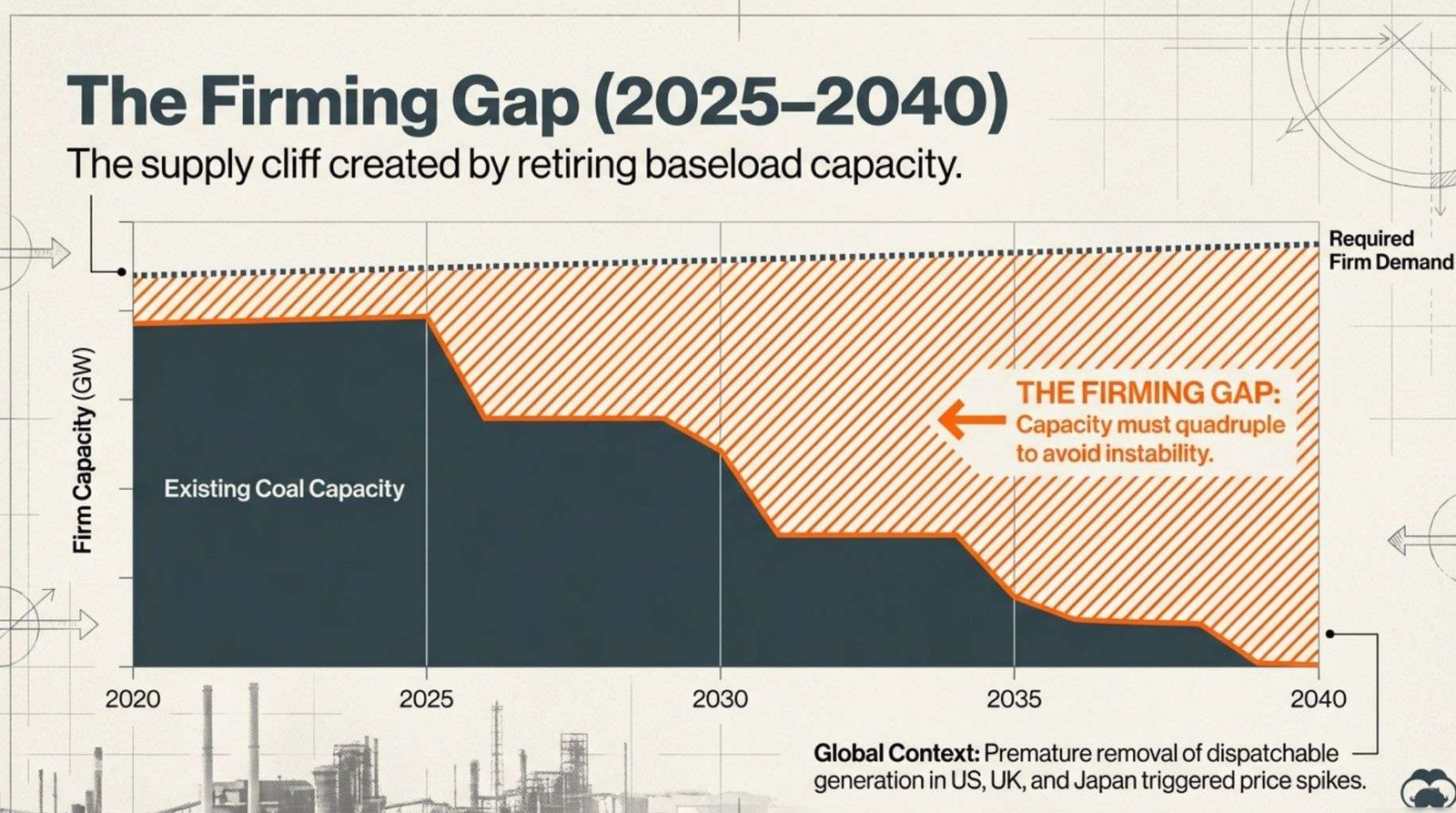

In the Australian Energy

Market Operator’s (AEMO) 2024 Integrated System Plan (ISP), firming was

identified as essential for system reliability.

Even under high renewable,

net-zero scenarios, AEMO forecasts that firming capacity from gas, hydro and

storage must roughly quadruple by 2040 to offset the retirement of 90% of the

existing coal fleet.

That transition presents

challenges. The US, UK and Japan have experienced that removing dispatchable

generation faster than firm replacement capacity can trigger instability,

blackouts, or inflationary price spikes.

Australia shows early

symptoms of similar strain. The response requires building a realistic bridge

using high-efficiency coal and gas at appropriate sites, upgraded hydro where

geography allows and a deliberate pivot to nuclear energy as the long-term

anchor.

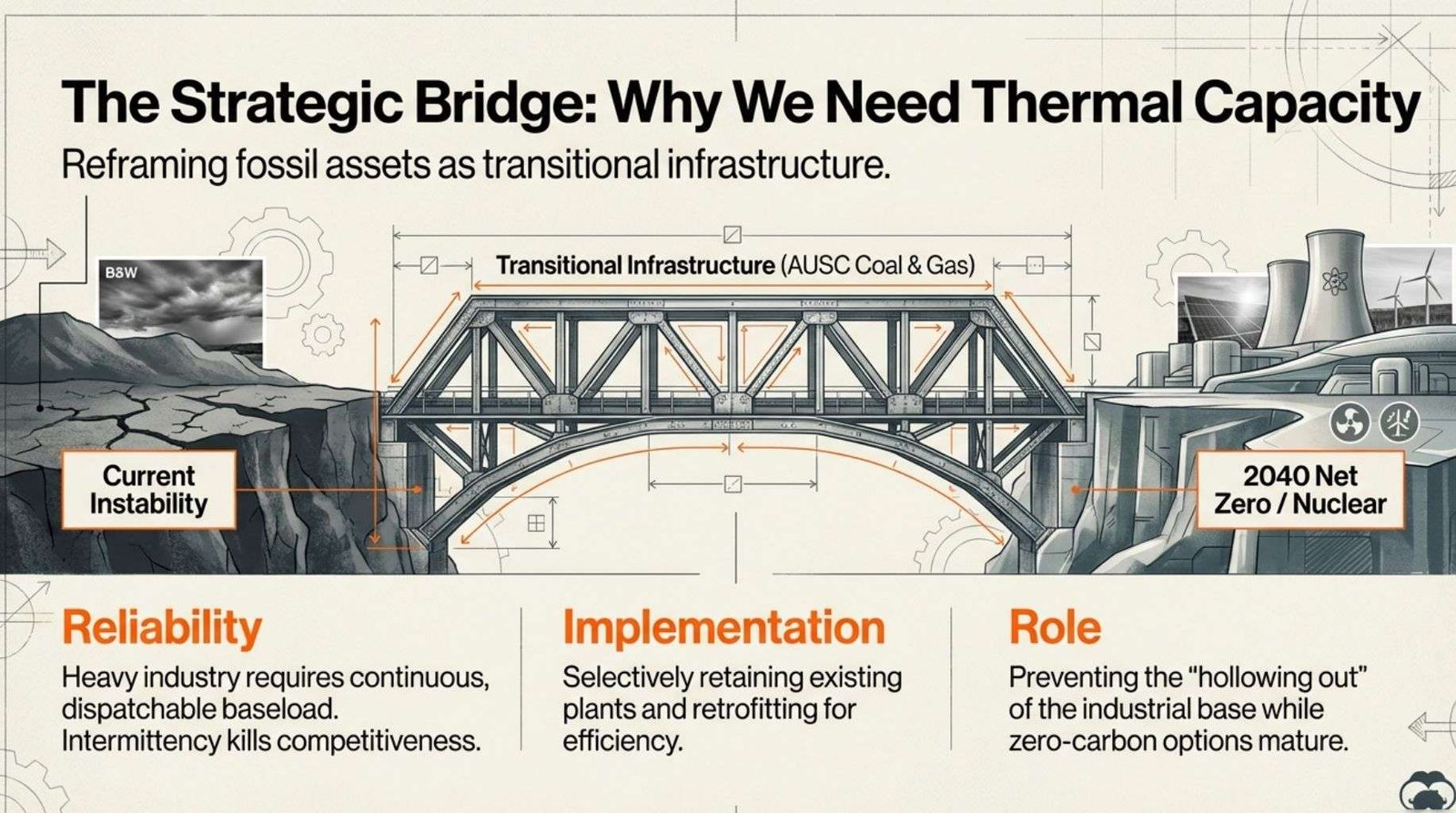

3. Bridging to the 2040s:

AUSC, HELE and Gas.

Between now and the early

2040s, high-efficiency low-emissions (HELE) coal, advanced ultra-supercritical

(AUSC) systems and open-cycle gas turbines will remain central to ensuring

continuous supply.

These technologies deliver

large-scale firming power at relatively low capital cost and high efficiency.

They also preserve

valuable labour skills, supply chains and grid topology while the next

generation of baseload, particularly nuclear, ramps up.

Policymakers should

consider treating modern fossil assets as transitional infrastructure essential

for industrial continuity rather than as competitors to decarbonisation.

The approach requires

appropriate timing and structure. Australia should selectively keep existing

plants online where safe and economic, retrofit them for efficiency or

emissions improvements and concentrate investment in regions already zoned and

grid-connected for heavy generation.

These upgrades act as

insurance, protecting the nation’s manufacturing base while longer-term

zero-carbon options mature.

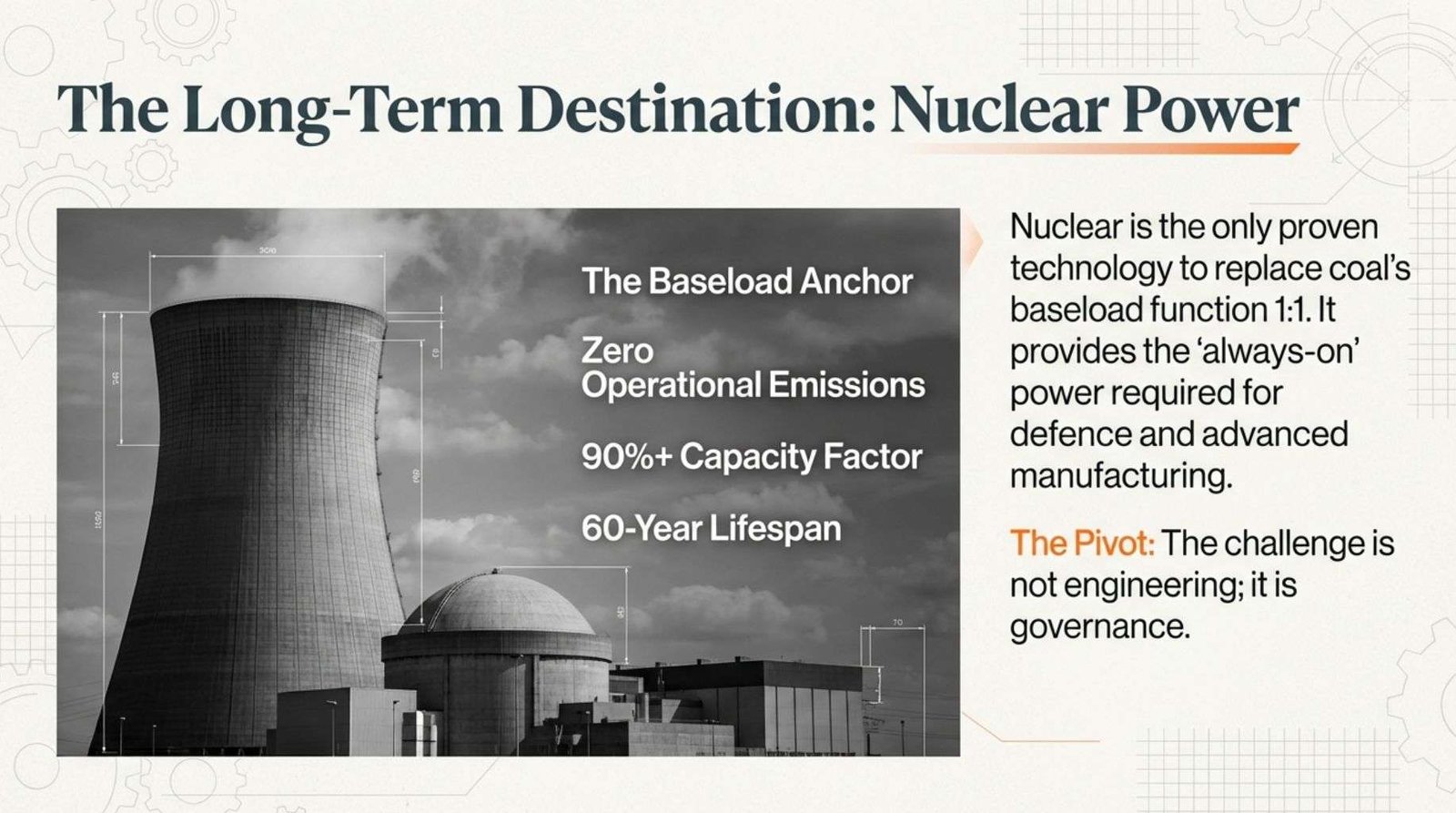

4. The Long Road to a

Nuclear Option.

Nuclear power is the only

zero-operational-emission technology currently proven to provide dense,

continuous baseload output.

Its global record, 90%+

capacity factors and multiple 60-year operational lifespans, demonstrates

performance. Deployment in Australia is complicated not by engineering but by

governance, law and time.

Two pieces of legislation

currently prevent progress:

1.

The Australian Radiation

Protection and Nuclear Safety (ARPANS) Act 1998, which prohibits the

Commonwealth from authorising construction of nuclear power facilities.

2.

The Environment Protection

and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act 1999, which specifically bans such

facilities under environmental law.

Repealing or amending

these involves parliamentary process, committee review and likely Senate

inquiry. Even if federal bans were lifted, each state would need to modify its

own prohibitions, which differ widely in scope.

Victoria, New South Wales

and Queensland currently legislate against nuclear power plants. South

Australia and Western Australia allow exploration of nuclear minerals but not

generation.

Legislating a path forward

means stepwise negotiation, one jurisdiction at a time, often tied to local

community benefits and regional energy needs. International experience suggests

this process alone can consume several years.

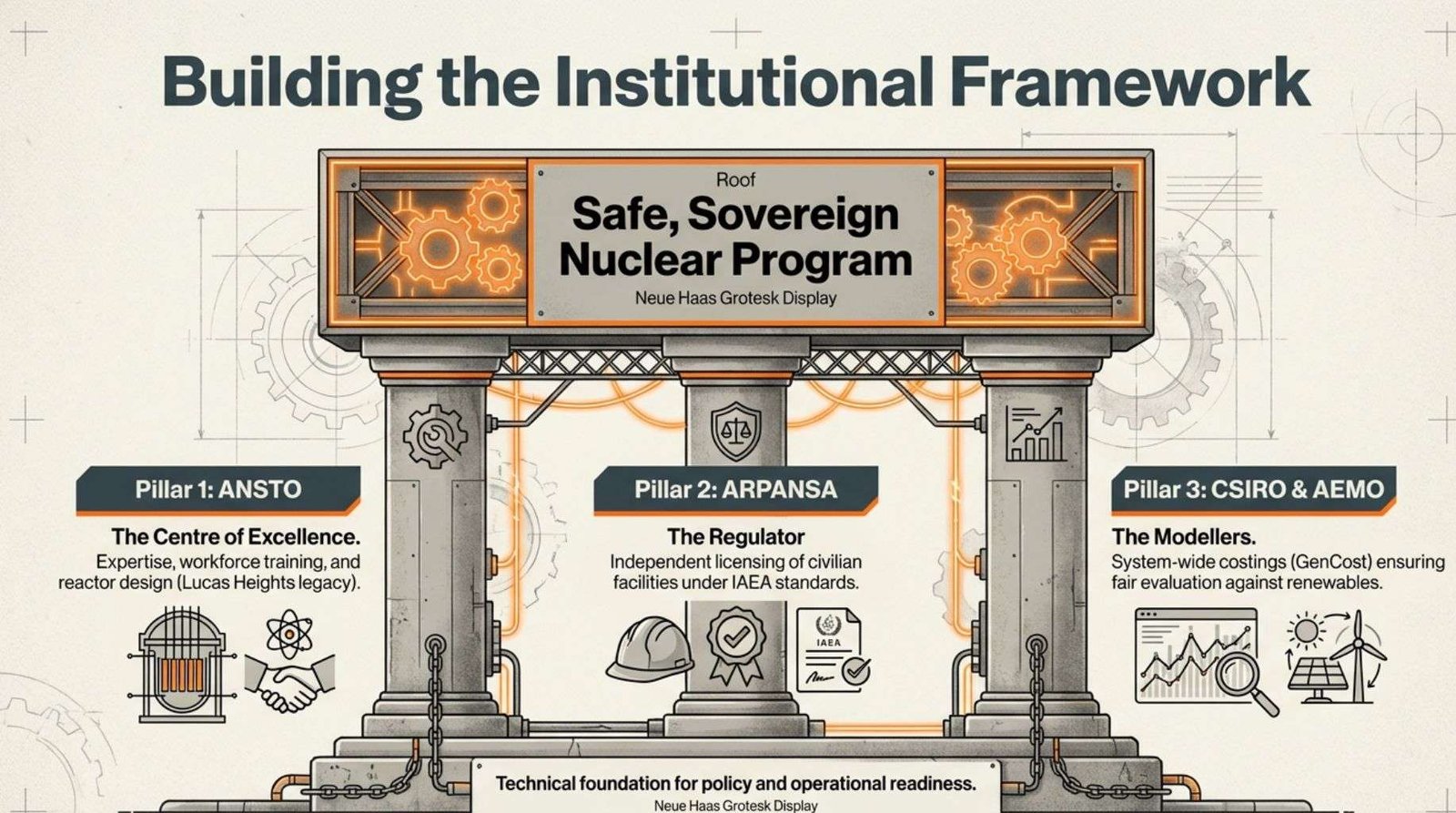

5. Building the

Institutional Framework.

Beyond law, institutional

architecture will define success. The most logical national structure builds

upon Australia’s existing scientific and regulatory pillars:

1.

ANSTO (Australian Nuclear

Science and Technology Organisation) should evolve into the government’s

central nuclear centre of excellence, responsible for technical expertise,

reactor design knowledge and workforce training. Its 60 years of safe reactor

operation at Lucas Heights provide a foundation.

2.

ARPANSA

(Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency) must remain the

independent, internationally aligned safety regulator. Its mission should be

expanded to license civilian nuclear facilities under globally recognised

standards such as those of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

3.

CSIRO and AEMO should

lead on system-wide costings and technology modelling. Through tools like

GenCost and the Integrated System Plan, they must ensure that nuclear is

evaluated on the same methodological footing as renewables, coal and gas.

This framework keeps

oversight balanced: ANSTO provides expertise, ARPANSA ensures integrity and

CSIRO and AEMO supply economic evidence.

Any federal government

will surely turn to CSIRO for cost comparisons, so nuclear should be integrated

responsibly into modeling rather than excluded.

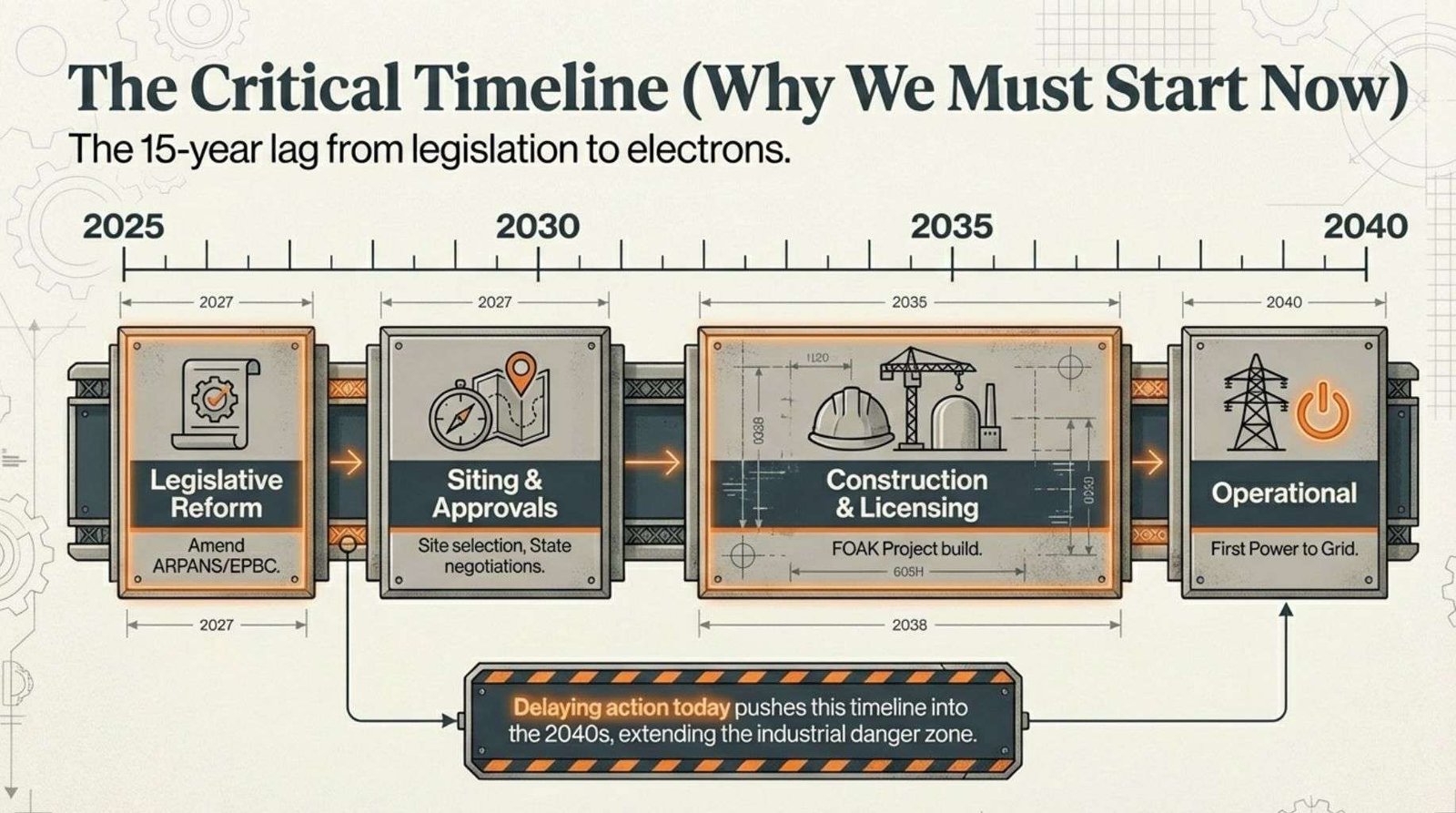

6. The Legal and Political

Roadmap.

The realistic pathway

follows this sequence:

1. Launch an Expert Review involving ANSTO, ARPANSA, CSIRO,

AEMO and major industry partners to map viable reactor types, costs and siting

options.

2. Amend Federal Legislation to remove prohibitions under

the ARPANS and EPBC Acts while ensuring ARPANSA’s authority is preserved.

3. Negotiate with States to modify or repeal state bans

through cooperative federalism, linking each change to potential local sites,

economic benefits and job creation.

4. Advance a First-of-a-Kind (FOAK) Project by selecting a

site with existing heavy industrial infrastructure, for instance, a retiring

coal station and progress through design, licensing, environmental assessment and

financing.

Even with ideal

coordination, the timeline from policy decision to first megawatt-hour of grid

electricity is typically ten to fifteen years.

This aligns with the

experience of nuclear newcomer nations such as Poland and the Czech Republic, which

began their modern programs in the 2020s with first generation expected in the

mid-2030s.

Fleet deployment, the

stage where nuclear meaningfully shifts national cost and emissions profiles, typically

follows another decade later. Delaying the outset of planning makes the task

harder later.

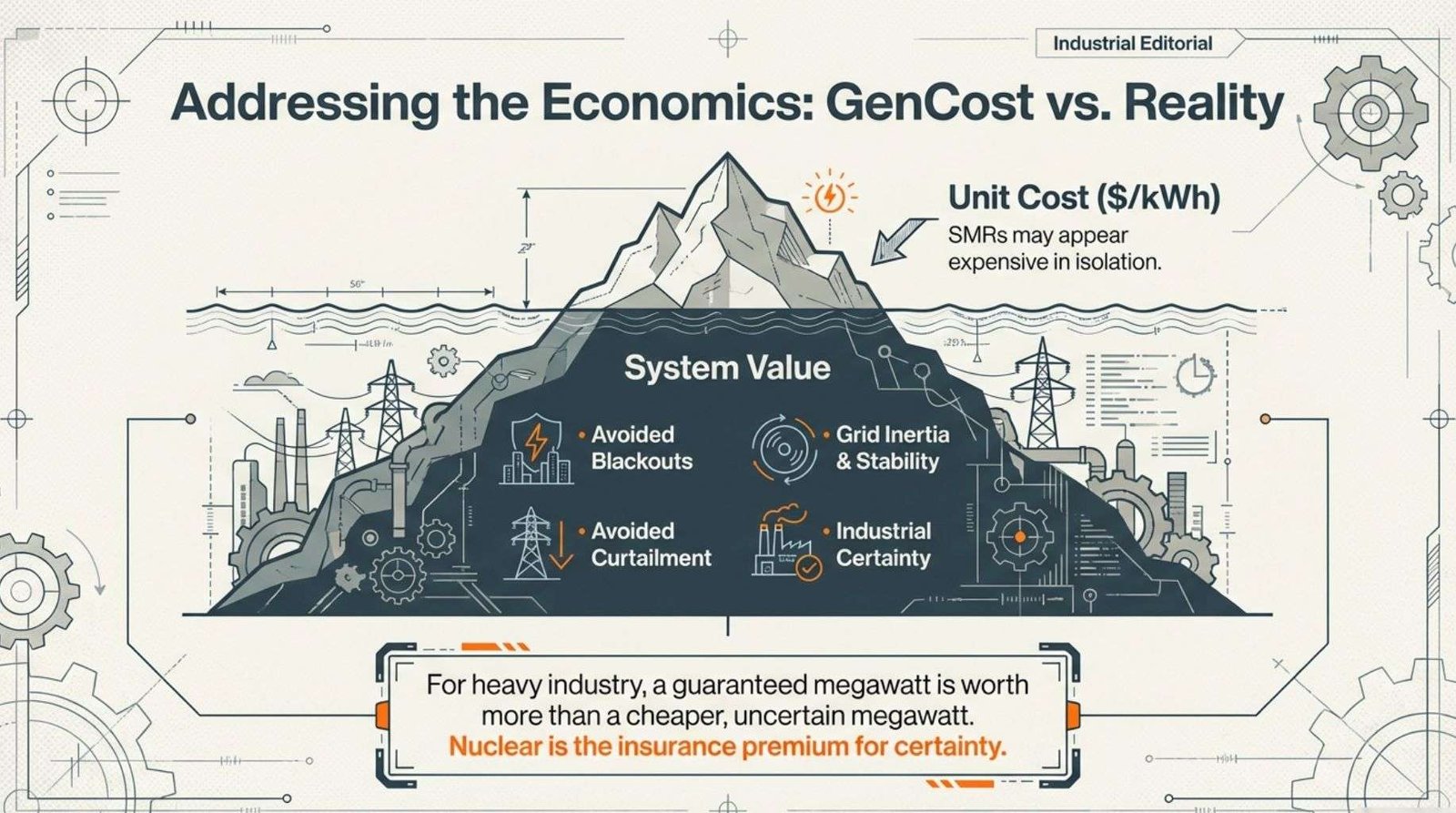

7. Integrating Economics

and Timelines.

Critics cite CSIRO’s

GenCost analyses to argue that nuclear remains high-cost. In raw dollars per

kilowatt-hour, small modular reactors (SMRs) are currently estimated 40-60% above

renewables with storage.

However, those figures

reflect assumption-heavy early designs without local supply chains or

nuclear-ready regulation. Historically,

unit costs fall steeply once the first plants are built and local capabilities

develop.

System value matters more

than plant-only cost. A grid with intermittent renewables and insufficient

firming experiences high volatility and curtailment, meaning periods of both

surplus and scarcity, each expensive in different ways. Nuclear’s strength

includes not only the energy it generates, but the stabilising effect it exerts

on wholesale prices and industrial certainty.

Industrial investors,

particularly in chemicals, hydrogen and critical minerals processing, value

predictable energy above all.

For them, a megawatt of

guaranteed supply is worth far more than a cheaper megawatt whose availability

is uncertain.

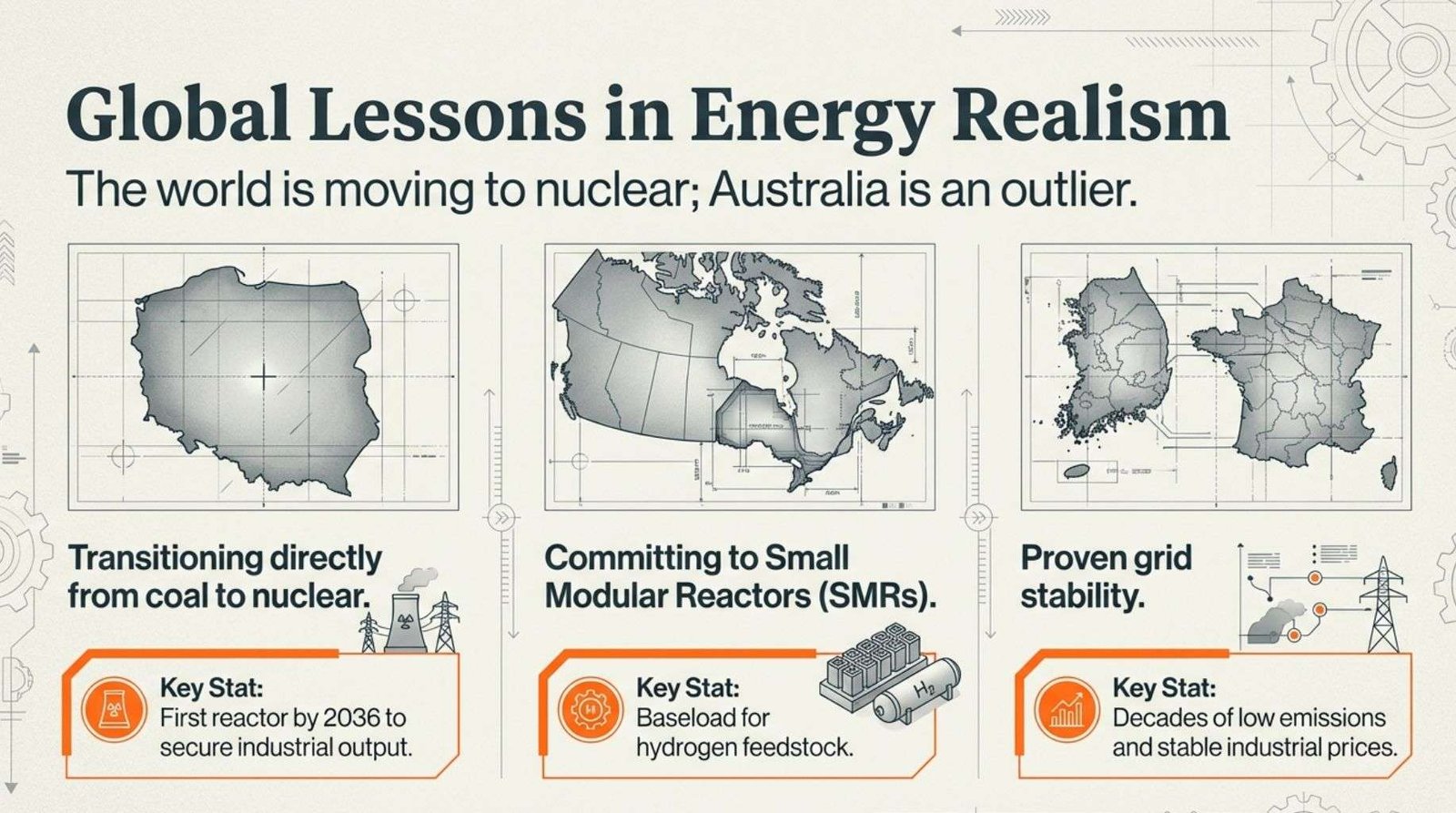

8. Global Lessons in

Energy Realism.

Other developed economies

provide instructive examples:

1.

Poland is transitioning

from coal to nuclear, targeting its first reactor by 2036 and achieving

industrial-scale nuclear output by the mid-2040s.

2.

Canada’s Ontario province

recently committed to multiple small modular reactors (SMRs) as both baseload

and hydrogen feedstock sources, citing round-the-clock energy needs.

3.

South Korea and France

have demonstrated that consistent nuclear programmes stabilise grid emissions

and industrial electricity prices simultaneously over decades.

Australia has spent nearly

25 years officially prohibited from even considering nuclear generation.

That lost time is now

being felt through escalating costs, declining competitiveness and dependence

on imported components for emerging sectors like electric-vehicle batteries and

green hydrogen.

9. Why Industry Should

Care Now.

The argument for nuclear

is industrial rather than ideological.

Without enormous,

continuous electricity at competitive prices, large-scale manufacturing will

remain uneconomic, regardless of tax incentives or sovereign capability

policies.

Energy-intensive industries

such as aluminium, steel, defence manufacturing and data processing require

multi-gigawatt-hour reliability.

Storage and renewables are

improving, but even optimistic projections rely on gigascale battery deployment,

an undertaking that carries its own material and environmental challenges.

Australia’s path forward

is not a binary choice between renewables and nuclear, or between gas and

storage.

It is a sequence:

renewables scale up where economic, transitional thermal capacity maintains

stability and nuclear begins the next era of baseload assurance. In parallel,

demand-side efficiencies and electrification expand but depend on the same

fundamental, abundant, steady energy.

10. The Political

Imperative.

The political challenge

involves sequencing reform while keeping public trust. Nuclear debates can

polarise communities, yet much hesitation stems from outdated imagery rather

than evidence of performance.

Modern reactors are

equipped with passive safety systems, inherently safe designs and multi-layer

containment unmatched in previous generations.

Transparency is essential.

By embedding ANSTO, ARPANSA, CSIRO, AEMO and independent experts in the process

from the outset, Australia can conduct a fact-based conversation grounded in

science, economics and public regulation.

Parliamentary inquiries,

rather than being obstacles, become vehicles to build legitimacy and record the

technical case for future parliaments.

11. Looking Fifteen Years

Ahead.

If serious policy

commitment were made during the current parliamentary term, by 2027, Australia

could feasibly see its first operating reactor around 2038-2040. By then,

almost all coal generation will be retired and reliable clean energy will

define the survival of heavy industry.

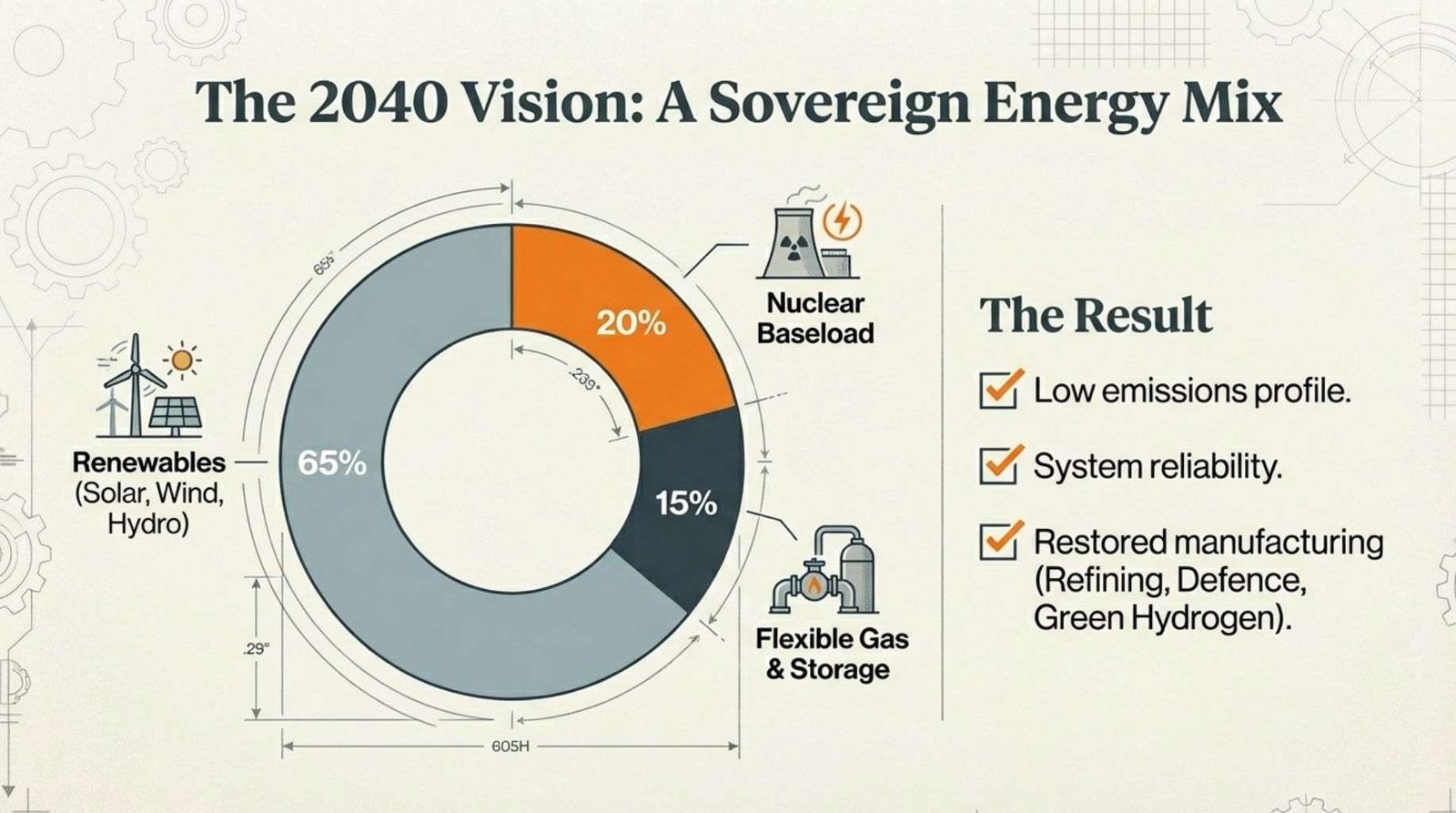

A balanced energy

portfolio in 2040 might include:

- Roughly 60-70% renewables (solar, wind, hydro).

- 10-20% flexible gas and storage.

- 10-20% nuclear baseload.

That mix can deliver both

low emissions and system reliability, anchoring industrial hubs across the east

coast and restoring confidence for long-life investments in refining,

manufacturing and hydrogen production.

12. Coal Is The Bridge To

Nuclear.

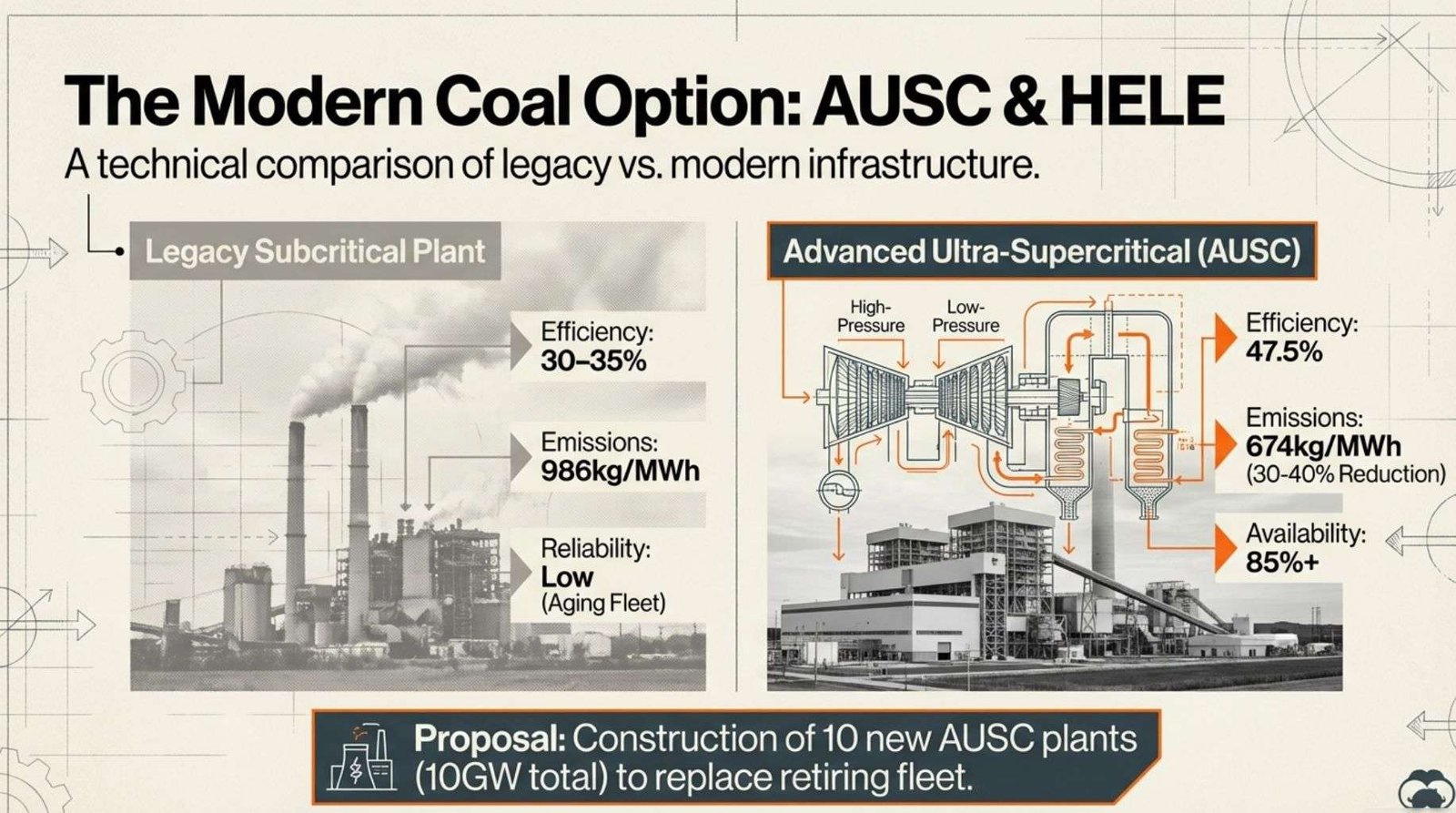

Building 10 brand new 3 to 4

GW Advanced Ultra‑Supercritical (AUSC) / HELE coal‑fired power stations,

each comprising 3 to 4 high‑efficiency units, would give Australia a stable,

affordable and strategically reliable energy backbone during the 10 to 15 years

required for nuclear power to scale.

These plants act as a

pragmatic transition technology, supporting the grid, protecting industry and

buying time for long‑term zero‑emission options to mature.

12.1.

Reliability Boost.

AUSC plants operate at 85%+ availability, delivering true

baseload power that far outperforms Australia’s aging subcritical fleet or

intermittent renewables without large‑scale storage.

With the existing coal

fleet suffering 128 breakdowns in a

single summer and units such as Gladstone running at 50% downtime, the construction of 10

x 3 to 4 GW AUSC stations (30–40 GW

total) would:

1.

Replace retiring coal

capacity before 2035.

2.

Add new firming capacity

to support population and industrial growth.

3.

Reduce AEMO interventions

that push wholesale prices higher.

Modern AUSC units can also

ramp quickly, enabling

smoother integration with solar and wind.

This flexibility becomes

essential as AEMO’s 2024 ISP anticipates 90%

of coal capacity retiring by the mid‑2030s, requiring a

fourfold increase in firming resources.

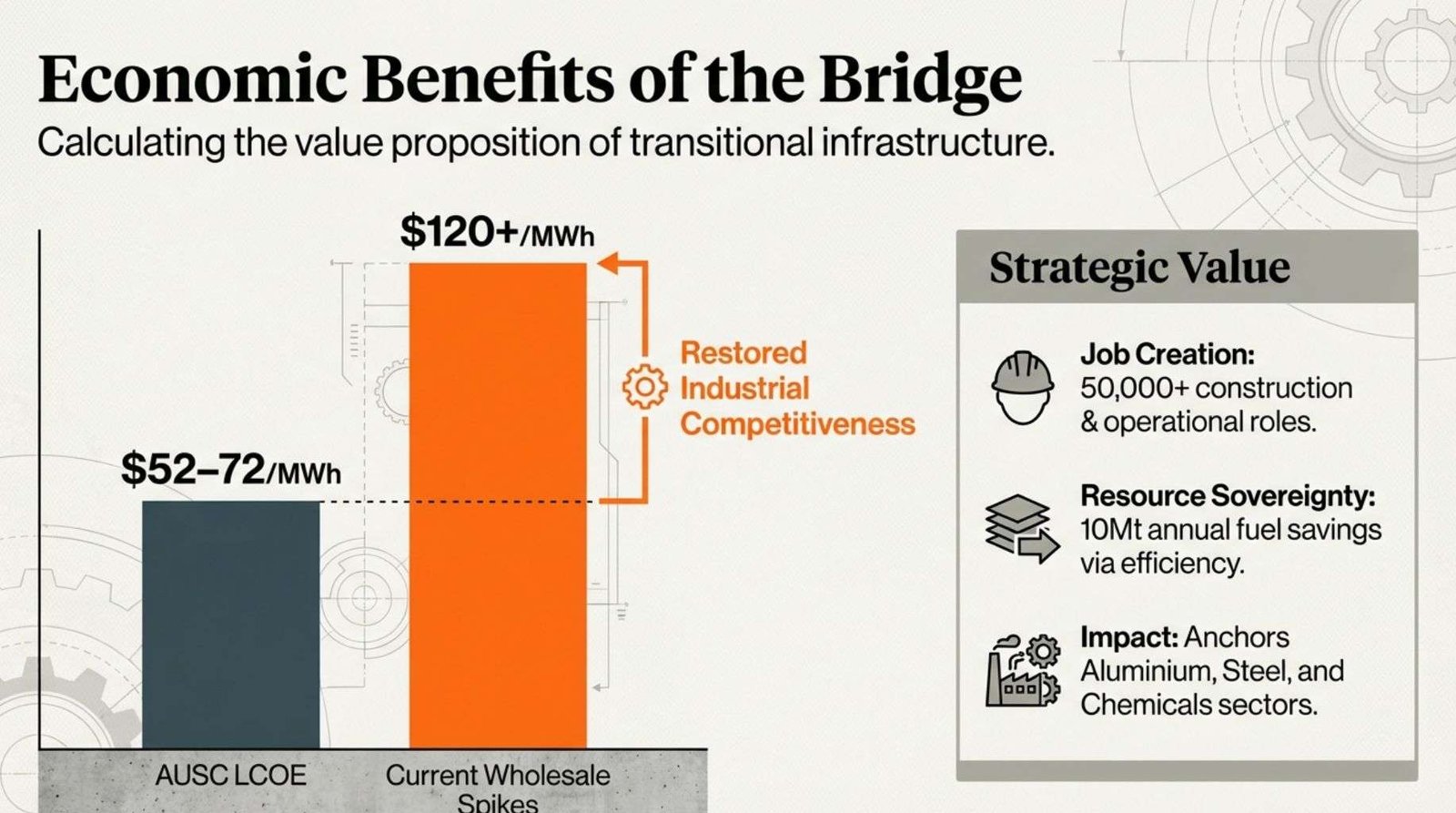

12.2.

Cost Stabilisation.

The LCOE of AUSC generation ($52–72/MWh)

is well below recent wholesale price spikes above $120/MWh. For energy‑intensive

industries, metals, chemicals, cement, fertilisers, this stability is critical,

especially after 27% real electricity

price increases since 2023 and more than 25,000 insolvencies linked to rising

operating costs.

Higher thermal efficiency

(up to 47.5%, compared

with 30–35% for legacy units) reduces coal consumption by roughly 1 Mt per GW per year. Across ten 3–4

GW plants, this equates to 30–40 Mt of

annual fuel savings, strengthening energy security by relying

on domestic reserves rather than imports.

12.3.

Emissions Reductions.

AUSC technology reduces

emissions intensity by 30–40%,

from around 986 kg/MWh

(subcritical) to ~674 kg/MWh.

Across 30–40 GW operating at 85%

capacity factor, this represents:

·

~70–95 Mt

CO₂ avoided annually, depending on final

capacity

·

Major reductions in NOx,

SOx, particulates and mercury

·

Lower health‑related

externalities, which legacy plants currently impose at an estimated $2.4B per year

Designing these stations

as CCS‑ready future‑proofs

them for carbon pricing and extends their operational relevance over the 40–50

year horizon while nuclear capacity ramps up.

12.4.

Industrial and Economic Gains.

|

Benefit |

Impact of 10 AUSC Plants (30–40 GW Total) |

|

Jobs |

50,000+ construction and operations roles;

preserves skilled labour for future nuclear deployment. |

|

Regional Development |

Revitalises Hunter Valley, Bowen Basin and

other coal regions by reusing existing grid, rail and port infrastructure. |

|

Industry Support |

Provides firm, affordable power for

aluminium, steel, data centres and critical minerals processing, helping

arrest manufacturing decline (now ~5% of GDP). |

|

Export Alignment |

Supports the $50B coal export sector and

its ~350,000 indirect jobs by maintaining domestic demand and skills

continuity. |

Locating new AUSC plants

at retiring coal sites, such as those in north Queensland, minimises

transmission upgrades and enables orderly phase‑out of inefficient units.

12.5.

Strategic Bridge to Nuclear.

Under the proposed

ANSTO–ARPANSA–CSIRO framework, Australia’s first nuclear output could

potentially be expected around

2038–2040 (with a bit of luck most likely also required)

AUSC plants provide the

firm thermal generation required to bridge this gap without immediate regulatory overhaul.

AEMO modelling indicates

that firm thermal capacity remains essential to 2040,

regardless of renewable penetration. Without it, Australia risks:

1.

Overbuilding renewables

and storage by 50–120%

to achieve equivalent reliability.

2.

Accelerating industrial

decline due to volatile energy prices.

3.

Increasing reliance on gas

peakers and imports.

AUSC therefore stabilises

the system while governments progress nuclear legislation (ARPANS Act

amendments, EPBC considerations) and negotiate state‑level approvals.

12.6.

Risks and Mitigations.

1.

Capital

Cost: AUSC requires $2–3B per GW, but competitive LCOE

and long asset life offset upfront investment. Government guarantees or

capacity mechanisms can de‑risk financing.

2.

Public

Perception: Opposition often stems

from legacy coal plants. Positioning AUSC as modern, high‑efficiency, 40% cleaner transitional infrastructure

reframes the narrative.

3.

Build

Time: AUSC plants can be delivered in 5–7 years, significantly faster than

nuclear’s 10–15 year timeline, enabling rapid reinforcement of the grid.

Summary.

10 x 3 to 4 GW AUSC/HELE

power stations would:

1.

Restore grid stability.

2.

Provide affordable

electricity for industry.

3.

Reduce emissions and coal

consumption.

4.

Support regional economies

and skilled workforces.

5.

Create a reliable bridge

to nuclear power.

This approach prevents

further de‑industrialisation and ensures Australia maintains energy security

while transitioning to long‑term zero‑emission technologies.

13. Balance: Industry,

Environment, Prosperity & The Cost of Living.

This article has tried to outline

a practical 15‑year pathway for Australia’s energy future, one shaped by

realism rather than rigid ideology.

It reflects the author’s

considered view that a sequenced transition can protect jobs, steady household

bills, reduce emissions and support a stronger industrial base. It isn’t

presented as a flawless blueprint; every energy strategy faces uncertainties,

from global supply chains to shifting policy settings.

Even so, the underlying

logic aims to speak to a broad set of interests: reliable power for industry,

meaningful decarbonisation for the environment, more predictable costs for

households and greater economic confidence for the nation.

The approach begins by

acknowledging the pressures facing Australian industry.

Many sectors require

dependable, around‑the‑clock energy to remain competitive and recent business

closures highlight the consequences when that stability falters. In this model,

advanced coal and gas technologies act as a transitional bridge through to

2040, offering firm supply while new systems scale up.

Environmental outcomes

also improve early in the transition. More efficient thermal generation reduces

emissions compared with older plants, while expanded firming capacity, consistent

with AEMO’s planning outlook, supports a higher share of renewables over time.

Beyond that horizon,

nuclear energy is positioned as a potential long‑term source of zero‑emission

baseload, drawing on international examples where it has delivered stable, low‑carbon

supply.

Prosperity is another

pillar. A managed transition helps retain specialised skills across

construction, operations and export‑linked industries, supporting regional

communities that have long contributed to Australia’s energy economy.

It also creates space for

emerging sectors, such as hydrogen, advanced manufacturing and defence, to grow

from a more stable energy foundation.

Finally, the cost‑of‑living

dimension is central. More predictable wholesale prices reduce the risk of

sharp spikes and help shield families from ongoing bill increases. Stable

energy costs underpin broader affordability and give households confidence to

plan beyond immediate utility pressures.

Taken together, this

balanced mix, transitional thermal generation, expanding renewables and a long‑term

nuclear option, aims to keep all stakeholders engaged in the journey.

The alternative is

continued uncertainty; the opportunity is a more resilient, more prosperous

Australia over the next 15 years (one can only hope).

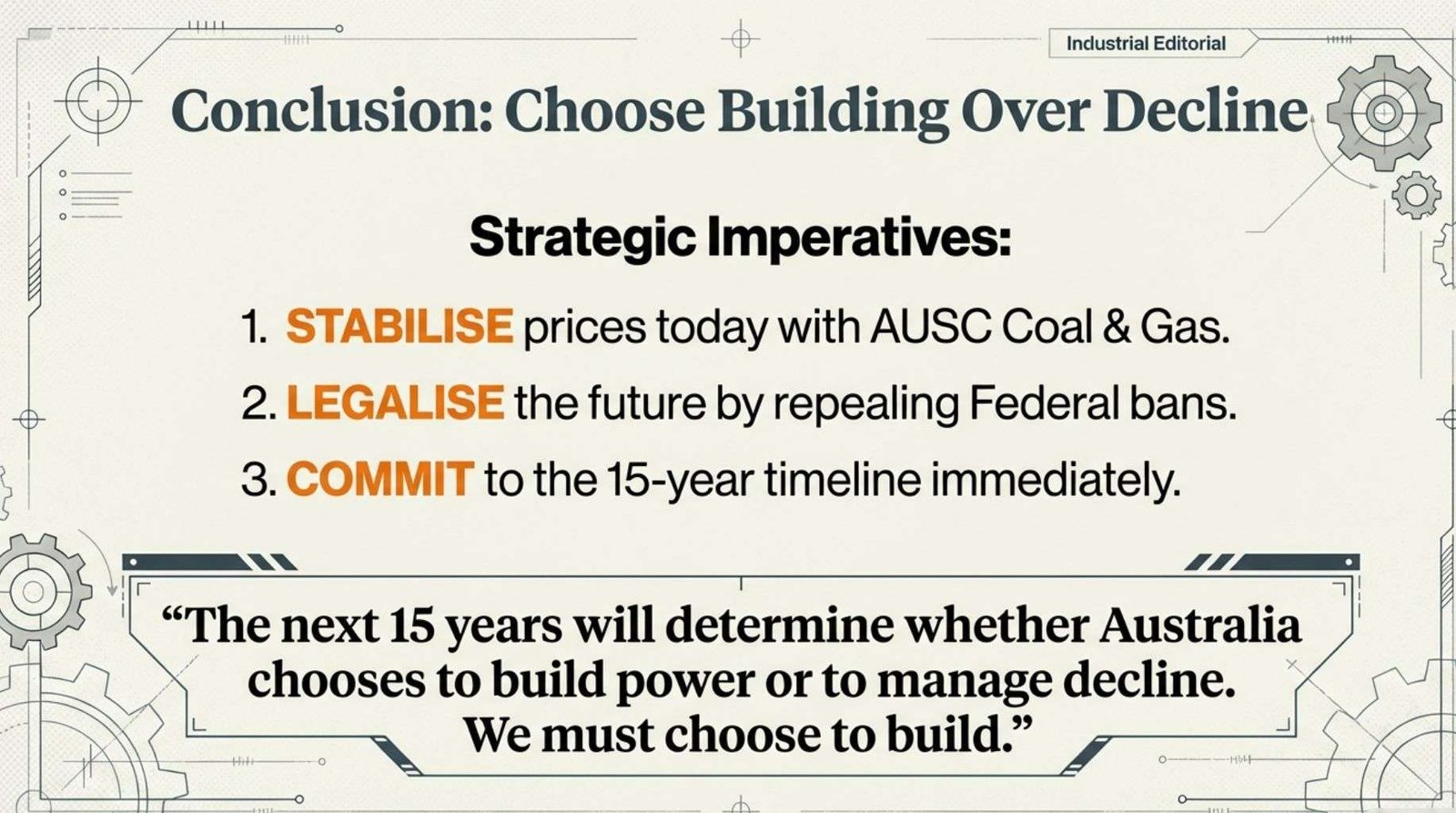

14. Conclusion: Choose

Building Over Decline.

Australia’s industrial

recovery depends on its willingness to face energy reality.

Cheap, round-the-clock

electricity is not optional; it is the foundation of modern sovereignty.

Without it, manufacturing, defence capability and advanced exports will

diminish.

The strategic path is

clear:

1.

Stabilise prices today

using efficient coal, gas and hydro where viable.

2.

Rebuild the institutional

and legal architecture for nuclear energy.

3.

Commit to an integrated,

long-term energy strategy where renewables and nuclear coexist to restore

national strength.

Every year of delay adds

years to recovery. The next 15 years will determine whether Australia chooses

to build power or to manage decline. With vision, pragmatism and institutional

focus, this energy transition can restore Australia’s place among the world’s

advanced industrial economies.

15. Bibliography.

1.

Australia’s Energy Transition: Policy and Regulation

Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), 2024.

2.

GenCost 2024-25: Electricity Generation Costs Update

CSIRO, 2025.

3.

Nuclear Power in Australia: Legal and Regulatory Barriers

Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency (ARPANSA), 2024.

4.

Coal Fleet Transition: Australia’s Power System to 2040

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, 2024.

5.

Firming the Grid: Storage and Dispatchable Power Needs

Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), 2025.

6.

AUSC Coal Technology: Efficiency and Emissions

International Energy Agency (IEA), 2023.

7.

Manufacturing

Decline: Australia’s Industrial GDP Share

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2025.

8.

Business Insolvencies 2023-2025: ASIC Data

Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), 2025.

9.

EPBC

Act and Nuclear Prohibitions

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, 2024.

10.

ARPANS

Act 1998: Nuclear Safety Framework

Australian Government, 2024.

11.

ANSTO

Nuclear Capabilities Report

Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO), 2025.

12.

Global

Nuclear Newcomer Timelines: Poland and Czech Republic

International Energy Agency (IEA), 2024.

13.

HELE Coal Retrofit Opportunities in Australia

Clean Energy Finance Corporation, 2023.

14.

AEMO Wholesale Electricity Market Report 2023-2025

Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), 2025.

15.

Industrial

Electricity Prices: International Comparison

International Energy Agency (IEA), 2025.

16.

Our

Plan for Zero-Emissions Nuclear Energy[australianeedsnuclear.org]

Australian Needs Nuclear, 2024.

17.

Australia’s Energy Transition: Policy Stocktake[researchers.mq.edu]

Macquarie University Researchers, 2025.

18.

Coal Gone by 2034: AEMO 2024 ISP[unsw.edu]

University of New South Wales, 2023.

19.

Will Australia Require Nuclear Energy?[studentorgs.kentlaw.iit]

Hemming, J., 2025.

20.

Nuclear Pathway Impact Assessment[climatechangeauthority.gov]

Climate Change Authority, 2025.

21.

Nuclear Power Inquiry Submission[climatecouncil.org]

Climate Council, 2025.

22.

Australia 2023 Energy Policy Review[iea.blob.core.windows]

International Energy Agency (IEA), 2023.

23.

Clean Energy Australia Report 2025[cleanenergycouncil.org]

Clean Energy Council, 2025.

24.

Coalition Nuclear Power Plan Explained[thedailyaus.com]

The Daily Aus, 2025.

25.

AEMO 2024 Integrated System Plan Full Report[australianphotography]

Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), 2024.

26.

CSIRO

GenCost Nuclear Analysis[capturemag.com]

CSIRO, 2025.

27.

ASIC Insolvency Statistics Mid-2023 to 2025[davidmagro]

Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), 2025.

28.

Manufacturing

GDP Share Record Low 2025[jaydidphoto]

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2025.

29.

Nuclear Legislation Reforms Needed[camblakephotography.com]

Australian Parliament, 2025.

30. Global AUSC Coal Deployments[adventureartphotography.com]

World Coal Association, 2024.