Redirect Global Resources Towards Humanity's Most Immediate Need.

Disclaimer.

This article presents analysis, observations and policy proposals regarding global homelessness and housing inadequacy.

The views expressed are intended to stimulate thoughtful discussion and reflection on resource allocation priorities.

Thoughts, opinions and ideas expressed are those of the author only.

This article does not constitute financial, investment, or business advice.

Readers are encouraged to conduct their own research and consult with qualified professionals before making decisions related to housing policy, charitable giving, or resource allocation.

Statistical data and cost estimates are based on publicly available research and are subject to variation across different contexts and timeframes.

Article Summary

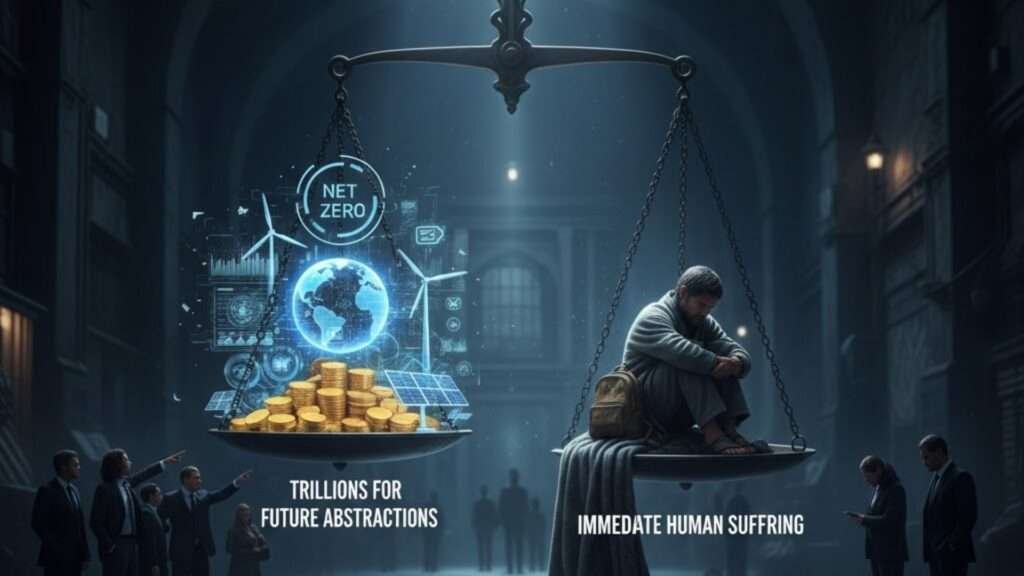

This article examines a profound and troubling disparity in global priorities.

While humanity mobilizes trillions of dollars to address climate change, a critical but long-term challenge, over 318 million people remain homeless and 2.8 billion lack adequate shelter.

The analysis reveals that solving chronic homelessness would require a fraction of current climate finance, yet housing receives minimal institutional support, fragmented funding and lacks the high-level governmental infrastructure dedicated to environmental goals.

Through comparative analysis of institutional frameworks, economic data and moral imperatives, this article proposes a paradigm shift: the establishment of a “Net Zero Homelessness” initiative that mirrors the scale, urgency and structural commitment currently reserved for carbon reduction.

The evidence demonstrates that housing is not merely a humanitarian concern but the foundational prerequisite for health, education, economic participation and social stability, making it an investment rather than an expenditure.

The path forward requires creating dedicated global institutions, reallocating a small percentage of existing resources and recognizing that a society’s true progress is measured not by its distant aspirations but by how it cares for its most vulnerable members today.

TOP 5 TAKEAWAYS.

1. The Scale of Disparity: Global climate finance reached $1.9 trillion in 2023, while ending chronic homelessness in the United States would require approximately $9.6 billion annually, less than 0.5% of climate funding. This reveals that homelessness is not unsolvable due to resource constraints but due to lack of prioritization.

2. Housing as Foundation: Adequate shelter is the prerequisite for all other human development, health, education, economic participation and dignity. Without this foundation, addressing any other global challenge becomes vastly more difficult and, for individuals, impossible.

3. The Cost of Inaction Exceeds the Cost of Solution: Studies show that allowing chronic homelessness costs approximately $35,578 per person annually in emergency services, healthcare and criminal justice, compared to $12,800 for supportive housing, making intervention not just morally imperative but fiscally responsible.

4. Institutional Architecture Determines Success: Climate change has dedicated ministries, regulatory bodies, multilateral funds and binding international agreements. Homelessness relies primarily on fragmented charitable efforts and underfunded local programs, explaining the vastly different outcomes despite comparable or lesser complexity.

5. The Moral Inversion: Society invests massively in protecting future generations from environmental harm while tolerating the immediate, preventable suffering of millions, including veterans and working families, who lack safe shelter today. This represents a failure not of resources but of empathy and institutional will.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

1.0 The Ultimate Contrast: A World Divided.

2.0 Housing as Humanity’s Foundation.

3.0 The Numbers That Reveal Our Priorities.

4.0 The Institutional Architecture of Climate Action.

5.0 The Fragmented Reality of Housing Advocacy.

6.0 The Economic Imperative: Why Housing Pays for Itself.

7.0 The Moral Failure: Heroes Left Behind.

8.0 Complexity as Cover for Inaction.

9.0 Envisioning a “Net Zero Homelessness” Initiative.

10.0 Global Coordination and the Habitat Fund.

11.0 Innovation: Engineering Dignity at Scale.

12.0 Policy Reform and the Right to Shelter.

13.0 The Dual Benefit: Housing and Climate Solutions Aligned.

14.0 A Five-Year Housing First Mandate.

15.0 The True Measure of Civilization.

16.0 CONCLUSION: The Choice Before Us.

17.0 Bibliography.

1.0 The Ultimate Contrast: A World Divided.

On any given night, while government officials gather in conference halls to pledge billions toward carbon neutrality targets decades away, more than 318 million people worldwide have nowhere to sleep.

No bed. No door to close. No address to call home. Meanwhile, 2.8 billion people, fully one-third of humanity, endure inadequate housing: slums where disease flourishes, informal settlements that wash away with each storm, structures that offer neither safety nor dignity.

The response to climate change has been extraordinary by any historical measure. Nations have established dedicated ministries, created massive regulatory frameworks and mobilized $1.9 trillion in annual financing. International summits command global attention.

Corporate boardrooms debate carbon neutrality as a reputational imperative.

The machinery of change, political, financial, technological, operates at full capacity, driven by the conviction that future generations deserve a livable planet.

This commitment deserves recognition. Climate change poses genuine, existential risks that require coordinated global action.

The innovation, cooperation and resource mobilization demonstrated by the climate movement represent humanity at its most forward-thinking.

Yet something profound has been overlooked. While we engineer solutions for atmospheric carbon levels in 2050, families sleep in their cars tonight.

While we debate the optimal carbon tax structure, children miss school because they have no stable place to study.

While we celebrate corporate net-zero pledges, veterans who served their nations endure the trauma of homelessness.

The contrast is not incidental; it reveals something fundamental about how societies organize their priorities.

It demonstrates that when political will exists, when institutions are properly structured, when resources are committed, humanity can move mountains.

The question this article explores is uncomfortable but necessary: If we can mobilize this capacity for a long-term environmental challenge, why can we not deploy the same energy, innovation and resources to solve the immediate crisis of homelessness?

What if the same institutional architecture, financial commitment and global coordination currently dedicated to achieving “Net Zero” carbon emissions were redirected, even temporarily, toward achieving “Net Zero Homelessness”?

What if every technological breakthrough, every policy innovation, every dollar of investment currently reserved for managing future climate risk were instead deployed to end the suffering happening right now, tonight, in every city across the globe?

2.0 Housing as Humanity's Foundation.

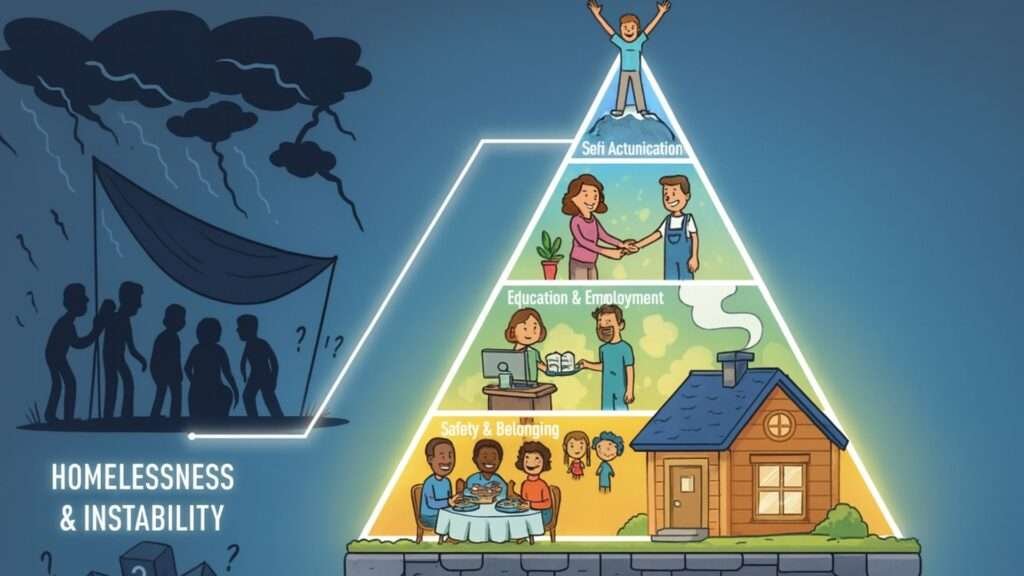

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, one of psychology’s most enduring frameworks, positions shelter as a fundamental physiological requirement, a prerequisite to every other form of human development.

This is not abstract theory; it reflects the lived reality of billions. Without safe, stable housing, nothing else becomes possible.

Consider the impossibility of the situation:

1. A mother cannot teach her children resilience when eviction looms tomorrow.

2. A young person cannot pursue education when exhaustion from sleeping rough makes concentration impossible.

3. A worker cannot maintain employment without an address for correspondence or a place to rest between shifts.

4. An individual cannot access healthcare, open a bank account, or participate meaningfully in civic life without the basic dignity of shelter.

Housing does not merely provide physical protection from the elements.

It serves as the foundation upon which every other dimension of human flourishing is built. The cascading effects of adequate housing touch virtually every social indicator:

1. Health and Survival: Inadequate housing breeds disease. Overcrowded conditions accelerate the transmission of tuberculosis, respiratory infections and waterborne illnesses. Lack of sanitation creates vectors for cholera and other preventable diseases. Mental health deteriorates under the constant stress of housing insecurity. Studies consistently show that homeless populations face mortality rates three to four times higher than housed populations. Stable housing, conversely, enables preventive care, medication compliance and the basic rest required for physical and mental recovery.

2. Education and Human Capital: Children experiencing homelessness face disrupted schooling, chronic absenteeism and educational delays that compound across years. The cognitive load of managing survival, worrying about safety, enduring hunger, lacking space for homework, makes learning nearly impossible. For adults, housing instability precludes access to training programs and skill development that could break cycles of poverty. Secure housing creates the stability necessary for educational investment, benefiting not just individuals but entire societies through enhanced human capital.

3. Economic Participation: Without a fixed address, individuals are effectively locked out of formal economic participation. Employers require addresses for applications. Banks require addresses for accounts. Government services require addresses for documentation. The inability to participate in the formal economy perpetuates poverty, reduces tax revenue and wastes human potential. Conversely, housed individuals can access employment, accumulate savings and contribute economically, transforming from net recipients of emergency services to net contributors to society.

4. Dignity and Mental Health: Perhaps the least quantifiable but most profound impact of homelessness is its assault on human dignity. The daily humiliation of visible destitution, the constant vigilance required for safety, the social isolation that comes from being visibly “other”, these exact an enormous psychological toll. Depression, anxiety and trauma become chronic conditions. Substance abuse often begins as self-medication for unbearable circumstances. The restoration of housing represents more than physical shelter; it represents the restoration of personhood, the acknowledgment that one’s life has value and deserves protection.

For nearly three billion people living in slums, informal settlements and inadequate dwellings, the concept of pursuing self-actualization, contributing to environmental stewardship, or engaging in long-term planning is almost absurd.

How can someone worry about future climate impacts when today’s storm might destroy their home? How can someone reduce their carbon footprint when basic survival consumes every resource?

Housing is not one priority among many; it is the foundation upon which all other priorities rest. Until this foundation is secured for everyone, other aspirations, however worthy, remain incomplete.

3.0 The Numbers That Reveal Our Priorities.

Abstract discussions of priority and principle gain clarity when examined through the lens of resource allocation.

The numbers tell a story that transcends rhetoric: they reveal what societies actually value through the choices they make about where to direct attention, funding and institutional power.

The climate mobilization has achieved remarkable financial scale. In 2023, global climate finance reached approximately $1.9 trillion, with projections suggesting this will rise to $2.3-2.5 trillion annually as nations work toward their net-zero commitments.

This represents an extraordinary marshaling of capital, involving government budgets, multilateral development banks, private investment and philanthropic contributions.

The financial infrastructure to support this mobilization includes specialized funds like the Green Climate Fund (with $19.3 billion in commitments), national climate banks, green bonds markets and carbon trading systems.

Private philanthropy alone contributes an estimated $7.5 to $12.5 billion annually to climate mitigation efforts.

This scale of investment demonstrates what becomes possible when an issue is framed as a global priority requiring urgent, coordinated action.

The climate movement has successfully convinced governments, corporations and individuals that near-term sacrifices and investments are justified by long-term benefits and risk mitigation.

Now consider the cost of solving homelessness.

Research examining the United States, one of the world’s wealthiest nations, suggests that addressing chronic homelessness nationwide would require approximately $9.6 billion in additional annual funding for Housing First programs and supportive services.

To put this in perspective: this represents less than 0.5% of annual global climate finance. The entire chronic homelessness crisis in America, affecting hundreds of thousands of people, could theoretically be addressed for a fraction of what the world invests quarterly in climate initiatives.

In the United Kingdom, estimates suggest that ending homelessness would cost approximately £1.9 billion ($2.3 billion). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the UK government spent over £480 billion on emergency response, making the cost of permanently solving homelessness less than 0.5% of pandemic spending.

The government demonstrated it could mobilize extraordinary resources rapidly when circumstances demanded; housing has simply not been framed as requiring the same urgency.

Perhaps most revealing is the cost comparison between action and inaction.

In the United States, studies indicate that chronic homelessness costs taxpayers approximately $35,578 per person annually through emergency room visits, ambulance services, psychiatric hospitalization, incarceration and police intervention.

Providing supportive housing, a permanent home with access to social services, costs an average of $12,800 per person annually.

The current approach of managing homelessness through emergency responses is nearly three times more expensive than solving it through housing provision, yet this costlier approach persists because the costs are distributed across multiple agencies rather than consolidated in a housing budget.

These numbers dismantle the argument that homelessness persists because solutions are unaffordable.

The resources exist; they are simply allocated elsewhere or spent inefficiently through crisis management rather than prevention.

The financial barrier to ending homelessness is not objective scarcity but political unwillingness to reorganize priorities and consolidate resources into a comprehensive solution.

The comparison is not intended to suggest that climate finance is wasteful or misdirected. Rather, it demonstrates that when societies decide something matters, they find the resources.

Climate change was reframed from an environmental concern to an existential threat and resources followed.

Housing remains framed as a charitable concern or individual failing rather than a structural crisis and resources remain fragmented and insufficient.

The question becomes impossible to avoid: If a fraction of 1% of climate finance could fundamentally address homelessness in wealthy nations and if solving homelessness is actually less expensive than allowing it to persist, why does the crisis continue?

4.0 The Institutional Architecture of Climate Action.

The success of any global initiative depends less on good intentions than on institutional architecture, the structures of governance, finance, enforcement and accountability that transform aspirations into outcomes.

The climate movement’s achievements stem not primarily from moral passion but from the systematic construction of powerful institutions dedicated to driving change.

Consider the governmental infrastructure. Across G20 nations, climate change occupies the highest levels of governmental attention.

Australia, for example, has established a comprehensive climate bureaucracy: the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water oversees national policy; the Clean Energy Regulator administers compliance and carbon markets; the Clean Energy Finance Corporation deploys billions in investment capital; and the Climate Change Authority provides independent advice on emissions targets and policy.

This is not a peripheral concern managed by a subdivision of another agency, it represents a parallel governance structure with dedicated authority, substantial budgets and direct ministerial responsibility.

This pattern repeats across developed nations. Cabinet-level ministers hold climate portfolios. Dedicated agencies enforce regulations.

Substantial staff expertise develops within government, creating institutional memory and technical capacity.

Climate considerations are integrated into economic planning, infrastructure development and foreign policy.

The institutional presence ensures that climate remains a consistent priority across election cycles and political transitions.

The financial architecture is equally sophisticated.

The Green Climate Fund represents a multilateral commitment to channel resources toward climate action in developing nations, with nearly $20 billion in commitments.

National climate banks and green investment funds provide patient capital for renewable energy, energy efficiency and climate adaptation projects.

Green bonds have become a major asset class, mobilizing private capital for climate-aligned investments.

Carbon pricing systems create market-based mechanisms for emissions reduction. Philanthropic organizations like those founded by Bezos, Bloomberg and Gates direct billions toward climate solutions annually.

This financial infrastructure creates multiple pathways for capital deployment, blending public and private resources, grants and investments, national and international funding.

The diversity of mechanisms ensures that climate finance can flow to wherever opportunities exist, whether funding cutting-edge technology, supporting behavior change, or building resilience in vulnerable communities.

The research and policy ecosystem provides the intellectual foundation.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change synthesizes scientific consensus and provides authoritative assessments that guide policy.

The Global Carbon Project tracks emissions with precision, holding nations accountable to commitments. Universities host dedicated climate research centers. Think tanks develop policy proposals.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change provides the diplomatic architecture for international negotiations, resulting in binding agreements like the Paris Accord that establish national commitments and create peer accountability.

This knowledge infrastructure ensures that climate policy is grounded in evidence, that progress can be measured, that best practices can be identified and disseminated and that the justification for continued investment remains scientifically credible.

The advocacy ecosystem spans from grassroots activism to corporate boardrooms. Organizations like 350.org and Greenpeace maintain global networks that pressure governments and corporations.

Youth movements like Fridays for Future generate media attention and political momentum. Investors increasingly demand climate risk disclosure and alignment with net-zero pathways.

Consumers express preferences for sustainable products. This multi-layered pressure from below and above, from citizens and capital markets, creates political incentives for leaders to take climate seriously.

Even opposition to climate action paradoxically reveals its institutional power. Fossil fuel interests spend hundreds of millions on lobbying and obstruction precisely because climate policy threatens their business models.

The American Petroleum Institute and similar organizations dedicate enormous resources to fighting climate regulation, an expenditure that only makes sense because climate policy has real institutional force.

The climate movement has constructed an ecosystem where success becomes structurally likely. Dedicated institutions ensure attention and resources. Financial mechanisms channel capital.

Research bodies provide legitimacy and evidence. International agreements create accountability. Advocacy maintains pressure. Media coverage ensures visibility.

This institutional architecture was not accidental or inevitable.

It was deliberately constructed through decades of advocacy, policy development and political negotiation.

It represents the crystallization of political will into durable structures that persist beyond individual leaders or moments.

The relevance to homelessness becomes clear: Without comparable institutional architecture, even the most compelling moral case struggles to translate into sustained action.

5.0 The Fragmented Reality of Housing Advocacy.

In stark contrast to the institutional machinery supporting climate action, efforts to address homelessness and inadequate housing remain fragmented, under-resourced and institutionally marginal.

This is not because the people working on housing issues lack dedication, competence, or moral clarity, it is because the structural support simply does not exist at comparable scale.

Housing typically appears as a subcategory within broader portfolios.

It might fall under social services, health departments, community development, or infrastructure ministries.

No G20 nation has established a standalone “Housing Security Authority” with powers and resources comparable to climate regulators.

Housing ministers, where they exist, rarely hold the same political weight as finance, defense, or increasingly, climate ministers.

The fragmentation means that housing competes for attention and resources rather than commanding dedicated commitment.

The financial architecture tells the same story.

While climate change can draw on trillions in annual investment through diverse mechanisms, housing for the homeless depends primarily on charity, limited government programs and sporadic development aid.

Organizations like Habitat for Humanity and World Habitat do vital work globally, but their combined resources are orders of magnitude smaller than multilateral climate funds.

They build homes one at a time or in small projects, constrained by donation cycles and volunteer capacity, while climate finance deploys billions through systematic investment vehicles.

UN-Habitat serves as the United Nations program for human settlements, but its role is primarily advisory and technical rather than involving massive capital deployment.

It can highlight the crisis, develop guidelines and support national planning, but it cannot mandate housing provision or deploy the kind of resources that flow through climate finance channels.

The Sustainable Development Goals include targets for adequate housing, but these lack the binding enforcement mechanisms and national reporting requirements of climate agreements.

Research on homelessness focuses heavily on documenting the problem, counting homeless populations, analyzing demographics, identifying contributing factors. Organizations like the Institute of Global Homelessness work to standardize definitions and measurement across nations, creating the evidence base for policy.

This work is essential but reveals the immaturity of the field: climate policy has long since moved beyond mere measurement to implementation at scale.

Housing advocacy still struggles to convince governments that the problem is real and measurable, while climate policy debates the optimal mix of technological solutions.

Advocacy organizations operate primarily at local and national levels. Groups like the National Alliance to End Homelessness in the United States or Housing Justice in the United Kingdom fight critical battles for funding and policy change, but they lack the global coordination, corporate engagement and cultural penetration achieved by climate advocacy.

There is no housing equivalent of the massive COP climate summits where national leaders gather annually, media coverage saturates public consciousness and commitments are announced with fanfare.

Corporate engagement with housing issues, where it exists, tends toward modest charitable contributions rather than the systemic integration seen with climate ESG commitments.

Companies proudly advertise their carbon reduction targets but rarely face questions about their contribution to housing affordability or homelessness. Investors do not yet demand “housing risk disclosure” the way they demand climate risk assessment.

This institutional deficit creates predictable consequences. Without dedicated agencies, housing lacks bureaucratic champions who fight for budget allocations and policy priority.

Without substantial financial mechanisms, interventions remain small-scale and precarious, vulnerable to budget cuts and political shifts.

Without binding international agreements, nations face no accountability for housing outcomes, no pressure to meet targets, no reputational cost for allowing homelessness to worsen.

Without coordinated research and policy development, best practices spread slowly, innovations remain isolated and the wheel gets reinvented repeatedly across jurisdictions.

Without powerful advocacy maintaining constant pressure, housing slips down the priority list whenever other crises emerge, while climate has achieved sufficient institutional embedding that it persists through crisis cycles.

The fragmentation means that even when solutions prove effective, they struggle to scale.

“Housing First” approaches, providing permanent housing without preconditions, alongside supportive services, have demonstrated remarkable success in multiple contexts, showing housing stability rates above 75% and dramatic improvements in health, employment and well-being.

Yet despite this evidence, Housing First remains the exception rather than the standard, implemented through pilot programs and limited initiatives rather than becoming the default approach, because there is no institutional mechanism to mandate adoption and fund implementation at scale.

The contrast with climate action could not be clearer: Climate has structure, housing has charity. Climate has ministries, housing has programs.

Climate has billions, housing has budgets. Climate has summits, housing has shelters. Climate has binding agreements, housing has aspirational goals.

This institutional deficit is not inevitable or natural. It represents a choice, implicit rather than explicit, about what deserves the full weight of governmental and international apparatus and what can be left to fragmented, voluntary efforts. Recognizing this institutional gap is the first step toward addressing it.

6.0 The Economic Imperative: Why Housing Pays For Itself.

One of the most persistent barriers to scaling housing interventions is the perception that doing so represents a net cost, an expenditure that, however morally justified, diverts resources from other priorities and burdens taxpayers.

This perception is not merely incorrect; it inverts the actual fiscal reality.

The evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that providing housing is not an expense but an investment that generates measurable returns.

The cost-benefit analysis begins with the current approach.

Emergency responses to homelessness, ambulances, emergency rooms, psychiatric hospitalizations, police interventions, incarceration, temporary shelters, are extraordinarily expensive precisely because they treat symptoms without addressing causes.

Each crisis generates immediate costs across multiple systems.

Emergency room visits alone are telling. Homeless individuals often lack access to primary care and preventive medicine, meaning conditions that could be managed cheaply spiral into medical emergencies.

A chronic condition that could be controlled with $50 of monthly medication instead requires a $2,000 emergency room visit, repeated multiple times.

Across the United States, studies estimate the average annual cost of emergency medical care for a chronically homeless person at approximately $7,000 to $10,000.

Psychiatric hospitalization adds substantial costs. The trauma and stress of homelessness precipitate mental health crises.

Without stable housing and consistent treatment, individuals cycle through crisis and stabilization.

Psychiatric hospitalization can cost $1,000 per day or more, with stays often lasting days or weeks.

Annual costs for individuals with serious mental illness who are homeless can exceed $20,000 in psychiatric care alone.

The criminal justice system bears enormous costs. Homelessness itself is often criminalized through laws against public sleeping, loitering, or camping.

Even absent these laws, survival behaviors, trespassing for shelter, theft of necessities, substance use, bring homeless individuals into repeated contact with police and courts.

Each arrest, prosecution and incarceration generates costs. The average cost of incarceration in the United States exceeds $35,000 per year.

Many homeless individuals cycle through repeated short-term incarcerations, each generating full processing costs without addressing underlying circumstances.

Combining these factors, comprehensive studies estimate that chronic homelessness costs between $35,000 and $45,000 per person annually in the United States, depending on jurisdiction and individual circumstances.

This cost is distributed across health, criminal justice, emergency services and shelter systems, making it less visible than a line item in a housing budget, but no less real to taxpayers funding these services.

Now consider the alternative. Providing permanent supportive housing, a subsidized apartment combined with access to healthcare, addiction treatment, employment support and social services, costs approximately $12,000 to $15,000 per person annually.

The housing itself might cost $8,000 to $10,000 in subsidy, with supportive services adding $2,000 to $5,000 depending on individual needs.

The fiscal arithmetic is straightforward: spending $12,000 to $15,000 on housing and support saves $20,000 to $30,000 in avoided emergency costs.

The return on investment ranges from 150% to 300%. This is not charity; it is among the highest-return interventions available to government.

These savings are not theoretical. Jurisdictions that have implemented Housing First at scale report measurable reductions in emergency service utilization, hospitalizations and incarceration among housed populations.

Studies from Utah, which nearly eliminated chronic homelessness through Housing First, documented precisely these savings.

Similar results appear in Canadian cities like Calgary, European programs and pilot initiatives globally.

Beyond direct fiscal savings, housing provision generates economic benefits. Housed individuals can seek and maintain employment, transitioning from benefit recipients to taxpayers.

They participate in consumer economies, supporting local businesses. They require fewer social services over time, freeing resources for others.

Children in stable housing attend school consistently, improving educational outcomes and future earnings potential, a long-term fiscal benefit as those children become productive adults rather than requiring ongoing support.

Construction and operation of housing creates employment directly. Building homes employs architects, construction workers, tradespeople and suppliers.

Operating supportive housing employs social workers, property managers and support staff. These jobs generate tax revenue and economic activity, offsetting program costs.

The broader economic argument extends beyond individual cost-benefit to societal productivity.

Homelessness represents wasted human capital, people capable of contributing who instead struggle merely to survive.

Skills atrophy, experience gaps widen, connections fray. Housing people does not merely reduce costs; it unlocks human potential, adding productive capacity to economies.

The fiscal case for housing investment is so overwhelming that the persistence of homelessness becomes economically irrational.

Governments are choosing the more expensive approach, managing chronic crisis, over the cheaper approach, providing stable housing.

This occurs because the costs of the current approach are distributed and hidden across many budget lines and agencies, while housing costs appear as a concentrated, visible expenditure.

The psychology of budgeting favors dispersed inefficiency over consolidated effectiveness.

Reframing housing as investment rather than expenditure requires making the cost comparison explicit and transparent.

It requires recognizing that every dollar spent housing someone saves multiple dollars elsewhere, that preventing homelessness is cheaper than managing it and that the status quo is the least fiscally responsible option available.

The economic argument for housing is not about affordability constraints; it is about the fiscal wisdom of prevention over crisis response.

7.0 The Moral Failure: Heroes Left Behind.

Numbers and institutional analysis capture important truths but can obscure the profound moral dimension of homelessness.

Some failures transcend policy and touch fundamental questions of honour, obligation and societal character.

Among the most troubling aspects of contemporary homelessness is whom it affects, not just the vulnerable we might expect societies to struggle serving, but individuals who have served those societies, who have fulfilled every expectation placed upon them and who have been abandoned despite their sacrifice.

Veterans represent the clearest indictment of misplaced priorities.

In Australia, research reveals that 5.3% of veterans who left military service between 2001 and 2018 experienced homelessness, nearly triple the general population rate of 1.9%, that’s a number we can truly be ashamed of.

These are individuals who volunteered for service, who endured training and deployment, who faced danger to fulfill national missions and who were promised care upon return.

These people run towards danger, towards the bullets, so that we don’t have to. Our demonstrated love and appreciation for our heroes leaves a lot to be desired.

Society’s failure to ensure their housing security represents not merely a policy failure but a betrayal.

The cognitive dissonance is extraordinary. Nations hold elaborate memorial ceremonies honouring service.

Politicians deliver speeches about debt to veterans. Governments spend billions on advanced weapons systems and military operations. Yet the men and women who operated those systems, who executed those operations, who protect our freedoms, keep us safe all year long and never get tired of protecting the country they love with all their heart, are sleeping in vehicles, shelters, or rough, at rates dramatically higher than the general population.

Post-traumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injuries, difficulty transitioning to civilian employment, these are the direct consequences of service. When these service-related challenges contribute to homelessness, society bears clear responsibility.

These are not random misfortunes but predictable outcomes of military service that societies promised to address. The failure to do so makes every memorial ceremony hollow, every pledge of support a lie.

The situation extends beyond veterans.

The rise of working homelessness reveals systemic failure affecting people actively contributing to economies and communities.

In Australia, the proportion of people seeking homelessness services who were employed rose from 10.9% to 15.3% in just three years.

These are not people who have “failed”, they are working, often in essential services, yet cannot afford basic housing.

The implications dismantle comfortable narratives about homelessness as primarily affecting those with addiction, mental illness, or inability to function.

While those populations certainly need support, the growing presence of employed, functional individuals in homelessness statistics proves this is a structural crisis of affordability and availability, not a crisis of individual failure.

When a nurse working hospital shifts sleeps in their car, when a retail worker cannot afford rent despite full-time employment, when families with working parents rely on shelters, the failure is not theirs but society’s.

The social contract promises that honest work provides basic security. When it does not, the contract is broken and the moral failure rests with those who maintain systems where work cannot secure shelter.

The presence of children in homelessness statistics carries particular moral weight. Children have no agency in their circumstances.

They did not make choices that led to homelessness; they inherited it. Every night children spend homeless represents pure, unambiguous suffering inflicted by societies with resources to prevent it.

The developmental damage, educational disruption, health impacts, psychological trauma, shapes entire lives, limiting potential and perpetuating cycles of disadvantage.

The moral arithmetic becomes impossible to avoid: When societies invest trillions in addressing long-term environmental risks while tolerating immediate suffering of those who served, those who work, those who have no agency, the priorities reveal something troubling about collective values.

The implicit message is that future abstractions matter more than present human beings, that statistical lives in climate models deserve more protection than actual lives struggling today.

This is not to suggest climate change is unimportant or unworthy of investment.

Rather, it suggests that the degree of investment in one area combined with neglect of another reveals an ethical failure, a willingness to mobilize resources for distant possibilities while accepting visible suffering as inevitable or unsolvable.

The moral case for prioritizing housing rests on the immediacy and severity of suffering, the direct ability to prevent it and the specific obligations owed to particular populations.

Veterans are owed care because of service rendered. Workers are owed security because of contributions made. Children are owed protection because of their vulnerability and innocence.

These are not complicated moral questions requiring sophisticated ethical frameworks. They are basic questions of honour, reciprocity and human decency. Societies that fail them, while maintaining capacity to mobilize trillions for other purposes, are societies that have lost clarity about fundamental priorities.

The emotional resonance of this failure should provoke discomfort.

That discomfort is appropriate. It should motivate reflection on whether current priorities align with stated values, whether distant concerns should outweigh immediate obligations and whether societies are worthy of the sacrifices made on their behalf if they abandon those who sacrificed.

8.0 Complexity As Cover For Inaction.

When confronted with the scale of homelessness and the clear disparity in resources, a common response emerges: housing is complicated.

Homelessness involves multiple overlapping challenges, mental illness, addiction, trauma, unemployment, disability, family breakdown.

Solutions, we are told, require nuanced, individualized approaches and long-term support.

The implication is that while the problem is regrettable, it is simply too complex for the kind of large-scale, systematic intervention that works for more straightforward challenges.

This argument deserves examination. Homelessness is indeed complex. Many individuals experiencing homelessness face multiple, intersecting challenges that cannot be solved by housing alone.

Severe mental illness requires ongoing treatment. Addiction benefits from comprehensive support. Trauma needs therapeutic intervention. These realities are not in dispute.

What deserves scrutiny is the selective deployment of complexity as justification for inaction. Consider climate change, the challenge currently receiving trillion-dollar systematic intervention.

Climate involves interconnected Earth systems, atmospheric chemistry, ocean dynamics and ecological feedbacks that scientists study using some of humanity’s most powerful computers.

Addressing it requires coordinating nations with competing interests, transforming global energy systems worth tens of trillions of dollars, developing technologies that do not yet exist at scale, changing consumption patterns across billions of people and managing transition impacts on workers and communities dependent on fossil fuel industries.

International climate negotiations involve nearly 200 nations with vastly different development levels, historical responsibilities and climate vulnerabilities attempting to reach binding agreements.

Carbon markets require sophisticated monitoring, reporting and verification systems to prevent fraud.

Energy grid transformation involves complex engineering challenges of integrating intermittent renewable generation with reliability requirements. Climate adaptation requires understanding localized vulnerability and building resilience across diverse contexts.

This is staggering complexity, arguably far greater than homelessness, yet complexity has not paralyzed action. Instead, it has motivated the creation of sophisticated institutions, attracted top researchers and justified massive expenditures precisely because the problem is complex and important.

The difference in response reveals that complexity itself is not the barrier.

Rather, complexity serves as a convenient excuse when political will is absent and as a motivating challenge when political will exists.

Climate change complexity justified creating elaborate institutional machinery; homelessness complexity justifies fragmented charity and modest programs.

This selective interpretation appears elsewhere. COVID-19 presented extraordinary complexity, novel pathogen, uncertain transmission dynamics, no existing treatments, unprecedented global spread.

Yet within months, governments mobilized trillions for emergency response, funded accelerated vaccine development, implemented mass testing and contact tracing and accepted economic disruption to protect public health.

The United Kingdom alone spent over £480 billion on pandemic response. Complexity did not prevent action; urgency demanded action despite complexity.

The comparison to homelessness is instructive. Ending homelessness in the UK would cost approximately £1.9 billion, less than 0.4% of pandemic spending.

If complexity were the actual barrier, pandemic response would have been impossible.

Instead, the pandemic was framed as requiring immediate, comprehensive intervention regardless of complexity, while homelessness is framed as too complex for comprehensive intervention.

The selective deployment becomes even clearer when examining responses to homelessness itself. When COVID-19 emerged, cities rapidly housed homeless populations to prevent transmission, demonstrating that the logistical capability exists when deemed necessary.

Temporary hotel accommodations, rapid rehousing programs and emergency shelters appeared within weeks. This revealed that the limiting factor was never logistical capacity or programmatic complexity but priority and political will.

Moreover, evidence increasingly shows that the most effective homelessness interventions are actually simple in concept: provide housing first, without preconditions, then offer support services.

This “Housing First” approach has been tested extensively across diverse populations and contexts, consistently demonstrating success rates that exceed traditional models requiring sobriety or treatment compliance before housing provision.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses show Housing First achieves housing stability rates of 75-88% even among populations with severe mental illness, addiction and long histories of homelessness.

This is not marginal improvement; it is transformative success with precisely the populations deemed “too complex” for housing interventions.

The model works because it recognizes that housing stability is the foundation that makes addressing other challenges possible, not a reward for having already addressed them.

The complexity argument thus reveals itself as cover for inaction rather than genuine barrier.

If homelessness were approached with the seriousness, resources and institutional commitment applied to climate change or pandemic response, complexity would motivate sophisticated intervention rather than justify neglect.

The selective framing, climate complexity demands action, homelessness complexity permits inaction, exposes the real issue: not capability but priority.

The working homeless population further undermines complexity narratives.

When employed individuals cannot afford housing despite full-time work, the problem is not individual complexity but structural failure.

No amount of addiction treatment, mental health services, or job training addresses the fundamental issue: housing costs exceed what work pays.

This is a straightforward economic problem with straightforward solutions, increase housing supply, regulate rents, raise wages, or subsidize costs.

The persistence of working homelessness proves that even the least complex form of homelessness goes unsolved when institutional will is absent.

The question societies face is not whether homelessness is complex, it is, but whether complexity justifies inaction or demands intervention.

The answer given for climate, for pandemics, for financial crises and for countless other challenges has been that complexity demands intervention.

Only for homelessness does complexity become an excuse.

This reveals not a principled stance on complexity but a selective application of concern that reflects priorities rather than capabilities.

9.0 Envisioning A "Net Zero Homelessness" Initiative.

If the climate movement demonstrates how societies mobilize when political will exists, the path forward for homelessness becomes clear: replicate that institutional architecture, resource commitment and political urgency for housing.

This would not require inventing new frameworks but rather adapting proven models to a different challenge.

The concept of “Net Zero Homelessness” serves not as metaphor but as blueprint, a call to apply the same systematic approach to housing that has been applied to carbon.

The vision begins with clear, measurable, binding targets.

Climate policy succeeds partly because nations commit to specific emissions reductions by specific dates, creating accountability and enabling progress measurement.

A Net Zero Homelessness initiative would establish similar commitments: every nation pledging to end chronic homelessness within five years, to ensure adequate housing for all within ten, with progress measured and reported annually.

These targets would not be aspirational goals buried in development plans but binding commitments integrated into national policy at the highest levels.

Just as nations submit Nationally Determined Contributions for climate, they would submit Housing Security Plans detailing how they will achieve zero homelessness, what resources they will deploy and what institutional reforms they will implement.

The initiative would recognize different national contexts and starting points, allowing flexible pathways to the shared goal.

Wealthy nations would commit to eliminating homelessness entirely while supporting global efforts.

Developing nations would commit to phased improvements in housing adequacy with international support.

The principle would be universal: every government accepting responsibility for ensuring its population has safe, dignified shelter.

Progress would be tracked through standardized metrics, not just counting rough sleepers but measuring housing adequacy, security of tenure, access to water and sanitation and protection from forced eviction. International bodies would verify reporting, identify best practices and provide technical assistance, creating peer accountability and facilitating learning across contexts.

The parallel to climate extends beyond targets to institutional structure.

Just as climate has its international agreements, housing would have a Global Housing Accord establishing the right to adequate housing as legally binding obligation, not merely aspirational principle.

This accord would create enforcement mechanisms, dispute resolution processes and consequences for failure, transforming housing from charitable concern to legal requirement.

National implementation would require institutional transformation. Governments would establish dedicated Housing Security Authorities with powers comparable to climate regulators, able to set standards, enforce compliance, coordinate across agencies and deploy resources.

These authorities would operate at cabinet level, reporting directly to heads of government, ensuring housing receives attention comparable to economic policy or national security.

The initiative would integrate housing with climate and development planning, recognizing synergies between challenges.

Climate adaptation requires housing resilient to extreme weather. Climate mitigation benefits from energy-efficient housing.

Sustainable development requires adequate housing as foundation. Rather than treating these as separate priorities competing for resources, integrated planning would maximize co-benefits and efficiency.

Financial mechanisms would mirror climate finance structures.

A Global Housing Fund, capitalized with mandatory contributions from wealthy nations and voluntary contributions from corporations and philanthropies, would deploy resources where need is greatest.

National housing investment banks would provide patient capital for housing development.

Tax incentives would encourage private sector participation. Innovative financing, social impact bonds, housing microfinance, community land trusts, would supplement traditional funding.

The scale of finance would reflect the scale of need and the proven returns on investment. If climate mobilizes $1.9 trillion annually, housing could justify $200-300 billion globally, enough to dramatically accelerate progress while remaining a modest fraction of climate finance.

This would not represent new burden on global economy but redirection of existing expenditures from crisis management to prevention and solution.

Technology and innovation would receive the kind of attention currently reserved for renewable energy and carbon capture.

Research institutions would focus on ultra-low-cost, rapidly deployable, climate-resilient housing technologies.

Competitions would drive innovation in sustainable materials, modular construction and off-grid infrastructure.

Open-source designs would accelerate dissemination.

The goal would be reducing housing cost and construction time dramatically while improving quality and sustainability.

Private sector engagement would shift from charity to integration. Just as companies now report climate risk and set emissions targets, they would report housing impact and set contribution goals.

Corporations would be evaluated on whether their operations support housing affordability, whether wages enable housing, whether developments include affordable units, whether supply chains strengthen local housing capacity.

This integration into corporate governance and investor expectations would harness market forces rather than relying solely on government action.

Civil society and advocacy would maintain pressure and accountability, but would operate within a framework where success is structurally supported rather than perpetually fighting for recognition.

NGOs would shift from service provision and emergency response toward policy advocacy, implementation support and innovation, with their survival not dependent on demonstrating ongoing crisis but on achieving measurable progress toward shared goals.

The Net Zero Homelessness initiative would ultimately represent a reframing: from treating housing as welfare for the unfortunate to recognizing it as infrastructure essential for functioning societies, from seeing homelessness as inevitable complexity to understanding it as solvable crisis, from accepting chronic suffering to demanding zero tolerance for preventable deprivation.

This vision is not utopian fantasy. Every element, binding targets, international agreements, dedicated institutions, substantial finance, technological innovation, corporate integration, exists already for climate.

The vision simply proposes applying these proven tools to housing.

The question is not whether this approach could work but whether societies will choose to deploy it.

10.0 Global Coordination and the Habitat Fund.

Transforming the vision of Net Zero Homelessness from aspiration to reality requires financial architecture capable of deploying resources at scale.

The climate movement offers a clear model: the Green Climate Fund, capitalized through mandatory national contributions and designed to channel billions toward climate mitigation and adaptation in developing nations.

A parallel structure for housing, a Global Habitat Fund, could similarly mobilize resources for housing infrastructure and homelessness elimination worldwide.

The case for such a fund rests on several foundations. First, housing inadequacy and homelessness are global phenomena requiring global response.

While specific solutions must be locally appropriate, the underlying challenge, insufficient resources combined with lack of political prioritization, appears consistently across contexts.

Wealthy nations struggle with urban homelessness despite overall prosperity; developing nations face massive housing deficits constraining development.

A global fund could facilitate resource transfer from surplus to need, technology sharing across contexts and coordination of efforts for greater impact.

Second, housing represents a global public good in ways that transcend national borders. Housing stability prevents displacement and migration crises.

It enables pandemic response and disease control. It provides foundation for education and human capital development. It reduces conflict and instability.

The benefits of ensuring adequate housing globally accrue not just to individuals housed but to international community through reduced crisis, enhanced stability and expanded human potential.

Third, the scale of need requires pooling resources.

While individual nations might address their own homelessness, the global housing deficit, particularly in rapidly urbanizing regions of Africa and Asia, exceeds what any single nation or even regional grouping can address alone.

Collective action enables addressing challenges that would overwhelm individual actors. The structure of a Global Habitat Fund could draw directly from climate finance precedents.

Capitalization would come from mandatory contributions by wealthy nations based on GDP or other capacity measures, supplemented by voluntary contributions from corporations, philanthropies and individuals.

Initial capitalization might target $100 billion, growing to $200-300 billion annually over five years, substantial but far smaller than climate finance and proportional to the cost of addressing global housing needs.

Governance would balance donor input with recipient voice, ensuring resources flow toward genuine priorities rather than donor preferences.

A board representing contributing nations, recipient nations, civil society and technical experts would establish funding priorities, approve major initiatives and ensure accountability. Independent evaluation would assess impact and identify effective approaches.

Funding would support multiple intervention types.

Core infrastructure grants would finance water, sanitation and energy systems essential for adequate housing.

Housing construction financing would provide capital for large-scale development of affordable housing, with repayment from rents or sales making funds revolving rather than pure grants.

Emergency response funds would address displacement from disasters, conflicts, or economic shocks.

Technical assistance would build capacity for housing policy, urban planning and program implementation.

Importantly, the fund would not simply build houses but address systemic barriers to housing adequacy. Land tenure reform receives funding when insecure tenure prevents housing investment.

Regulatory reform receives support when excessive restrictions limit housing supply. Community organizing receives resources when grassroots mobilization is necessary for policy change.

The approach recognizes that housing inadequacy stems from multiple causes requiring diverse interventions.

The fund would explicitly integrate housing and climate goals.

Financing would prioritize climate-resilient housing in vulnerable areas, energy-efficient design to reduce emissions, sustainable materials to minimize environmental impact and compact urban development to reduce sprawl.

This integration creates dual benefits, addressing housing needs while advancing climate goals and demonstrates that these challenges need not compete but can be tackled simultaneously.

Private capital mobilization would be central to the fund’s strategy.

Public resources alone cannot address global housing needs, but they can catalyse private investment by reducing risk, providing guarantees, or co-financing projects.

Blending public and private capital, the fund could multiply its impact beyond direct expenditures, channelling trillions in private investment toward housing infrastructure.

Beyond the Global Habitat Fund, national and regional financing mechanisms would be necessary.

National housing investment banks could provide patient, low-cost capital for housing development, supplementing market financing.

Regional development banks could coordinate housing initiatives across borders, addressing transnational urbanization and displacement. Municipal housing funds could enable local governments to address specific community needs.

Innovative financing mechanisms could supplement traditional funding. Social impact bonds could engage investors willing to accept returns tied to housing outcomes, homelessness reduction, health improvements, education gains.

Housing microfinance could enable low-income families to incrementally improve their housing through small loans.

Community land trusts could separate land ownership from housing, reducing costs and ensuring permanent affordability.

The financial architecture would ultimately need to be comprehensive, involving public and private resources, grants and investments, international and domestic funding.

The goal is not to create a single massive fund but to establish an ecosystem of financing that ensures resources flow reliably toward housing at scale sufficient to address need.

Climate finance demonstrates that such mobilization is possible. The Green Climate Fund alone has committed nearly $20 billion, while total climate finance approaches $2 trillion annually.

Housing requires less absolute resources but similar systematic commitment. The question is not financial feasibility, the money exists, but political willingness to construct the institutions that deploy it.

11.0 Innovation: Engineering Dignity at Scale.

One of the most promising aspects of the climate movement has been its catalyzing of extraordinary technological innovation.

Renewable energy costs have plummeted, battery technology has advanced dramatically, electric vehicles have become competitive and carbon capture approaches are scaling.

This innovation resulted not from passive market forces but from deliberate policy support, targeted research funding, demonstration projects and market-creating regulations that made sustainable technology economically viable.

The same innovative energy could transform housing if directed toward that challenge.

The goal would be developing housing approaches that are simultaneously affordable, rapidly deployable, environmentally sustainable, culturally appropriate and dignified, meeting multiple objectives rather than trading them off.

Material innovation offers immediate opportunities. Traditional construction relies heavily on concrete and steel, both carbon-intensive and expensive.

Research into alternative materials, engineered wood, compressed earth blocks, bamboo composites, recycled materials, bio-based materials, could reduce costs and environmental impact while maintaining quality.

Advanced materials like self-healing concrete, super-insulating aerogels, or phase-change materials for temperature regulation could enhance performance.

Construction methodology presents another frontier.

Modular construction, building housing components in factories then assembling on-site, can dramatically reduce construction time and cost while improving quality control.

Three-dimensional printing technology enables constructing homes in days with minimal labor, potentially revolutionizing housing provision in resource-constrained contexts. Prefabricated systems allow rapid deployment while accommodating diverse designs and local preferences.

The potential for innovation extends to integrated systems.

Housing need not be merely shelter but could incorporate water harvesting, solar generation, waste treatment and food production, creating self-sufficient or semi-autonomous systems particularly valuable in areas with limited infrastructure.

Designing housing as integrated systems rather than just buildings could reduce ongoing costs and environmental impact while enhancing resident security.

Digital technology enables innovation in housing access and management. Platforms connecting available housing with those seeking it could reduce friction and vacancy.

Blockchain-based land registries could secure tenure in contexts where traditional systems are weak.

Digital housing vouchers could increase portability and choice. Remote monitoring could enable predictive maintenance, reducing costs.

The goal is applying technology to reduce barriers and improve efficiency rather than as an end in itself.

Design innovation addresses social and cultural dimensions.

Housing must be not just physically adequate but culturally appropriate and dignity-affirming. Participatory design processes engage future residents in shaping their housing.

Flexible designs accommodate diverse family structures and preferences. Community-oriented design fosters social connection rather than isolation.

The innovation is not merely technical but social, ensuring housing solutions meet human needs beyond just shelter.

Financing innovation could expand access. Incremental housing approaches allow families to build progressively as resources permit rather than requiring full cost upfront. Rent-to-own programs create pathways from renting to ownership.

Shared equity models allow partial ownership with opportunity to buy out. Cooperative housing models enable collective ownership and management.

The variety of approaches acknowledges that one size cannot fit all situations.

Importantly, innovation must be not just technological but also policy innovation. Simplified regulatory approval processes could reduce development costs and delays.

Community land trusts could remove land cost from housing equations, ensuring permanent affordability. Inclusionary zoning could leverage private development to create affordable housing.

Value capture mechanisms could fund housing from infrastructure improvements. Social housing at scale could provide alternatives to market-only approaches.

The innovation ecosystem would require certain elements to thrive. Research funding would support basic and applied research into housing technologies, materials and approaches.

Demonstration projects would prove concepts and refine implementations before scaling. Knowledge sharing platforms would disseminate successful innovations across contexts.

Competitions and prizes would incentivize breakthrough solutions. Standards and certifications would ensure quality while enabling innovation.

Universities and research institutions currently studying climate technology could equally focus on housing innovation.

Engineering schools could prioritize affordable housing design. Business schools could develop sustainable housing finance models.

Architecture programs could emphasize dignity and cultural appropriateness. The talent and resources exist; they need direction toward housing challenges.

Corporate engagement could accelerate innovation. Construction companies could invest in new methodologies.

Material suppliers could develop sustainable alternatives. Technology companies could apply digital solutions.

Financial firms could create innovative funding mechanisms. Just as corporations now showcase climate innovation, they could similarly prioritize housing innovation, driven by market opportunity, policy incentives and reputational benefits.

The ultimate goal is reducing the cost and improving the quality of housing dramatically, making adequate housing affordable even in low-resource contexts while meeting sustainability standards and providing dignity.

This is not fantasy; it is straightforward application of human ingenuity to a clear challenge. The barrier is not human capability but whether societies choose to direct innovation toward this priority.

Climate change has proven that when humanity focuses its innovative capacity on a challenge, remarkable progress follows.

Solar and wind power went from niche to mainstream in two decades. Battery costs fell 90% in a decade.

Electric vehicles became competitive. These transformations resulted from sustained focus and investment. Housing could see similar transformation if given similar attention.

12.0 Policy Reform and the Right to Shelter.

Technology and finance, while essential, cannot alone solve housing crises without fundamental policy reforms addressing structural barriers to housing adequacy.

Many obstacles to adequate housing are not natural or inevitable but result from policy choices that could be changed.

A comprehensive housing initiative must therefore include ambitious policy transformation at local, national and international levels.

Land policy stands as perhaps the most critical reform area. In many contexts, land speculation and hoarding prevent housing development, driving prices beyond reach while land sits vacant.

Land value taxation, taxing land based on value rather than just improvements, could discourage speculation and incentivize development. Vacant property taxes could similarly mobilize underused properties.

Public land banking could reserve strategic sites for affordable housing rather than allowing private capture.

Secure tenure represents another fundamental need. Billions worldwide lack clear, legal ownership or tenancy of their housing, leaving them vulnerable to forced eviction and unable to invest in improving their dwellings.

Land registration programs could formalize tenure, particularly in informal settlements. Squatter rights recognition could acknowledge long-term occupation. Community land ownership could secure collective tenure. Legal aid could help vulnerable populations defend against unfair eviction.

Zoning and regulatory reform could dramatically increase housing supply and reduce costs. Exclusionary zoning that prevents multifamily housing in many urban areas artificially constrains supply and drives up costs.

Reforms allowing higher density, mixed-use development and diverse housing types could increase supply.

Streamlined approval processes could reduce development costs and delays. Building code reforms could enable innovative construction methods while maintaining safety.

Rent regulation addresses housing as ongoing cost beyond just initial access. While controversial, rent stabilization can prevent displacement and ensure housing remains affordable in expensive markets.

The key is designing policies that protect tenants without discouraging new construction, perhaps applying controls to existing housing while exempting new development for defined periods, or using means-tested vouchers rather than universal controls.

Anti-discrimination policies ensure that housing access is not denied based on race, ethnicity, religion, family status, or other protected characteristics.

While most jurisdictions have such laws, enforcement is often weak. Stronger enforcement mechanisms, testing for discrimination and penalties for violations could ensure laws have real effect.

Affirmative approaches might require diverse tenant selection in subsidized housing or incentivize development in segregated areas.

Eviction reform could prevent homelessness at the source. Many people become homeless through eviction for non-payment during temporary hardship. Emergency rental assistance during crisis could prevent eviction.

Right to counsel in eviction proceedings could ensure fair process.

Sealed eviction records could prevent eviction history from permanently limiting housing access.

The goal is viewing eviction as last resort rather than routine management tool.

Social housing at scale represents comprehensive policy approach. Rather than relying on private markets supplemented by limited subsidies, governments could develop and operate substantial housing stock available at below-market rates to those who need it.

Vienna’s model, where over 60% of residents live in social housing, demonstrates this need not be low-quality or stigmatized but can provide diverse, quality housing while ensuring affordability.

Housing First policies should become the standard approach to homelessness. Decades of evidence demonstrate that providing permanent housing without preconditions, combined with supportive services, effectively ends homelessness for most people.

Yet many jurisdictions maintain shelter systems that offer only temporary accommodation with requirements and rules that exclude many.

Shifting resources from shelter systems to permanent housing with support would be more effective and more humane.

International human rights frameworks could be strengthened. The right to adequate housing is recognized in international agreements but lacks strong enforcement.

A binding international protocol with reporting requirements, complaint mechanisms and consequences for violation could transform the right from aspiration to reality, similar to how human rights treaties influence behavior in other areas.

Financial sector regulation could address housing as investment versus housing as home.

Policies might limit corporate ownership of residential property, restrict short-term rentals that reduce long-term housing supply, or require institutional investors to maintain affordability.

The goal is ensuring housing serves primarily as homes for people rather than vehicles for wealth accumulation or speculation.

Integrated planning approaches could ensure housing is not addressed in isolation but coordinated with transportation, employment, services and infrastructure.

Transit-oriented development concentrates housing near public transportation. Mixed-income developments prevent segregation by class.

Co-locating services with housing creates accessible, walkable communities. The approach recognizes that adequate housing exists within a broader system.

Progressive realization principles acknowledge that housing rights cannot be achieved immediately everywhere but require continuous progress.

The legal standard would be that nations demonstrate year-over-year improvement toward adequate housing for all, with regression requiring justification. This creates accountability without demanding impossible immediate fulfillment, similar to how climate commitments accept transition periods while requiring progress.

All these policies share common features: they address systemic causes rather than just symptoms, they remove barriers rather than just offering support and they recognize housing as right and necessity rather than commodity to be accessed only by those who can afford market prices.

The policies are not radical or untested, many exist in various jurisdictions, but they require political will to implement widely and comprehensively.

The contrast with climate policy is again instructive.

Climate action has required fundamental policy transformation, carbon pricing, fossil fuel phase-outs, vehicle emission standards, renewable portfolio standards.

Societies accepted these transformative policies because climate was framed as requiring system change, not just incremental adjustment.

Housing needs similar framing: incremental programs layered on problematic systems will not achieve adequate housing for all. Fundamental policy reform is necessary and proven policies exist ready for implementation.

13.0 The Dual Benefit: Housing and Climate Solutions Aligned.

One potential objection to prioritizing housing over continued climate focus is that the two exist in tension, competing for limited resources and attention.

This framing is false. In fact, addressing housing inadequacy and advancing climate goals can be mutually reinforcing, with integrated approaches delivering dual benefits more efficiently than addressing each in isolation.

Consider the intersection at the most basic level: housing construction and operation represent significant portions of global energy use and emissions.

Buildings account for roughly 40% of global energy consumption and 30% of greenhouse gas emissions.

Addressing housing need through sustainable approaches could simultaneously expand housing availability and reduce emissions, a win on both dimensions.

Energy-efficient housing design reduces ongoing energy costs for residents while reducing emissions. High-performance insulation, passive solar design, efficient appliances and smart systems minimize energy requirements.

For low-income households, reduced utility bills make housing more affordable. For societies, reduced energy demand decreases infrastructure requirements and emissions. The climate and housing goals align perfectly: the same housing that addresses social needs also advances environmental goals.

Renewable energy integration creates similar synergy. Solar panels, heat pumps and other renewable systems can be incorporated into new housing development at lower cost than retrofit.

Distributed generation from residential sources reduces grid stress and transmission losses. Battery storage in homes provides grid flexibility.

Low-income housing could become leading edge of renewable adoption rather than lagging, with government financing enabling technologies that residents could not afford independently.

Material choices offer another area of alignment. Sustainable materials, engineered wood, compressed earth, recycled content, reduce embodied carbon in construction while often reducing costs.

Local materials reduce transportation emissions while supporting local economies. Bio-based materials sequester carbon while providing housing.

The same decisions that reduce climate impact often improve affordability and appropriateness.

Urban planning integration amplifies benefits. Compact, transit-oriented development reduces vehicle dependence and associated emissions while increasing housing density and affordability.

Mixed-use neighborhoods reduce travel distances while creating vibrant communities.

Green infrastructure manages stormwater while improving livability. The housing patterns that support climate goals also create more accessible, affordable and socially connected communities.

Climate adaptation and housing resilience intersect directly.

Climate change increases extreme weather, flooding and heat events, threatening inadequate housing most severely.

Housing improvements that enhance climate resilience, elevation, reinforcement, cooling systems, water management, protect residents while reducing disaster response costs.

Addressing housing inadequacy through climate-resilient approaches prevents future crises rather than requiring repeated rebuilding.

The economic arguments align as well. Sustainable construction creates jobs in growing sectors. Energy efficiency reduces long-term housing costs.

Renewable energy integration supports industry development.

The same investments that expand housing also advance the energy transition, with employment and economic benefits from both.

Social equity considerations unite the agendas. Climate change impacts fall most heavily on vulnerable populations, those least able to adapt, most exposed to hazards, most affected by displacement.