Trying To Understand Australia's Wild Coastal Weather.

Disclaimer.

This article provides general information about coastal weather patterns, climate variability, urban development and risk management in Australia.

It does not constitute professional advice for land‑use planning, property investment, engineering, climate science, or policy development.

Readers should seek guidance from qualified professionals and relevant authorities before making decisions related to coastal development, property purchases, infrastructure planning, or climate‑adaptation strategies.

Weather conditions, climate trends and regulatory frameworks vary by location and evolve over time.

The views and interpretations expressed are those of the author and are intended as broad commentary only. They should not replace site‑specific assessments or formal professional consultation.

Article Summary.

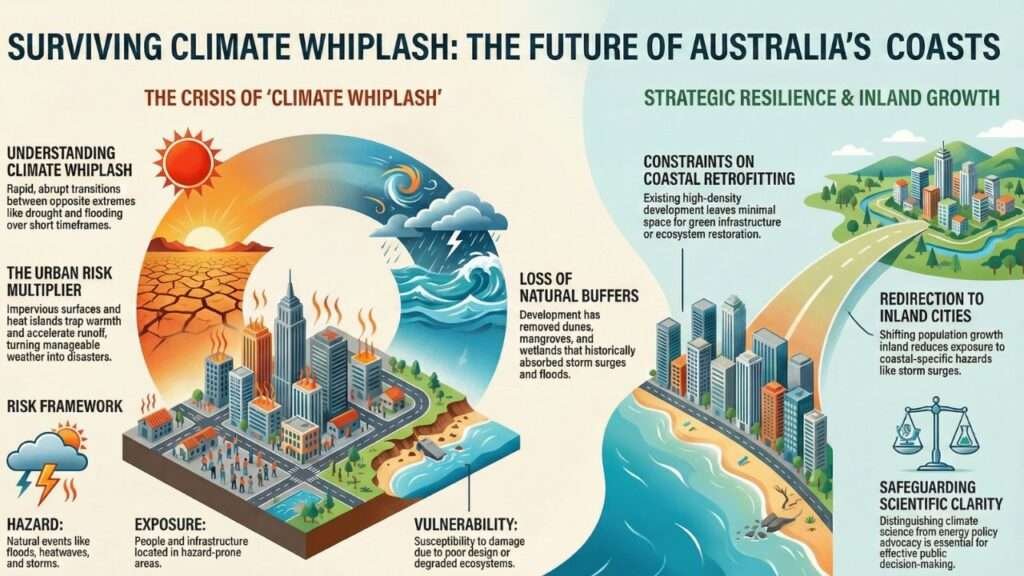

Australia’s coastal regions are experiencing increasingly volatile weather patterns characterised by rapid transitions between extreme conditions.

These shifts, sometimes described by researchers as “climate whiplash,” involve abrupt swings between drought, extreme heat and flooding over short timeframes.

While changing atmospheric and oceanic conditions contribute to this volatility, the severity of impacts is significantly amplified by decades of coastal urban development.

Metropolitan expansion across coastal plains has replaced natural buffers with impervious surfaces, creating urban heat islands that trap heat, alter local hydrology and increase flood risk.

The combination of natural climate variability and extensive coastal settlement has elevated exposure and vulnerability, transforming manageable weather events into costly disasters.

Limited remaining undeveloped coastal land constrains large-scale retrofitting options, suggesting that long-term resilience may require redirecting growth inland rather than solely improving existing coastal infrastructure.

Top 5 Takeaways.

1. Rapid weather transitions between drought, heat and flooding are occurring with increasing frequency across Australian coastal regions, with some scientists characterising these patterns as ‘climate whiplash’.

2. Urban development in coastal areas has significantly increased exposure and vulnerability by replacing natural buffers with impervious surfaces that create heat islands, accelerate runoff and remove protection against erosion and storm surge.

3. Risk in coastal regions results from the interaction of three factors: natural hazards, exposure created by development patterns and vulnerability from degraded ecosystems and infrastructure design.

4. Retrofitting existing coastal development faces severe constraints because most coastal land has already been developed, leaving minimal space for large-scale green infrastructure or water-sensitive redesign.

5. Long-term coastal resilience may require shifting population growth and economic development inland to areas with lower exposure, rather than relying solely on improving already-built coastal infrastructure.

Table of Contents.

1. Understanding Coastal Weather Volatility.

1.1. Climate Whiplash Defined.

1.2. Contributing Atmospheric and Oceanic Factors.

2. Urban Development and Amplified Risk.

2.1. Coastal Expansion Since the Mid-20th Century.

2.2. Urban Heat Islands and Altered Hydrology. 2.3. Loss of Natural Buffers.

3. The Risk Framework.

3.1. Hazard, Exposure and Vulnerability.

3.2. Compounding Factors in Coastal Australia.

4. Constraints on Coastal Adaptation.

4.1. Limited Space for Retrofitting.

4.2. The Case for Inland Development.

5. Separating Climate Science from Energy Policy.

6. Conclusion.

7. Bibliography.

8. Slides (Images)

1. Understanding Coastal Weather Volatility.

1.1. Climate Whiplash Defined.

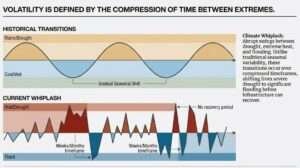

Rapid transitions between opposite weather extremes, occurring over short timeframes, are becoming more common across Australia’s coastal regions.

This pattern involves abrupt swings between drought conditions, extreme heat events and flooding.

Some climate scientists use the term “climate whiplash” to describe these accelerated oscillations between contrasting weather states and peer-reviewed research supports this characterisation.

The phenomenon differs from traditional seasonal variability. Rather than gradual transitions between weather patterns, coastal regions are experiencing compressed timeframes between extreme conditions.

A location may shift from severe drought to significant flooding within weeks or months, rather than the more extended transitions historically observed.

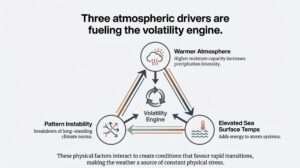

1.2. Contributing Atmospheric and Oceanic Factors.

Three physical mechanisms that contribute to increased weather volatility are:

1. Warmer air holds more moisture, increasing the potential for intense precipitation events when atmospheric conditions favour rainfall.

2. Elevated sea surface temperatures provide additional energy to weather systems, potentially intensifying storms and other meteorological events.

3. Certain long-standing climate patterns affecting Australia appear less stable than in previous decades, though the degree and causes of this instability remain subjects of ongoing research.

These factors interact to create conditions favouring greater volatility and more rapid transitions between weather extremes.

The extent to which each factor contributes varies by location and timeframe and uncertainty remains regarding long-term trajectory and regional variations.

2. Urban Development and Amplified Risk.

2.1. Coastal Expansion Since the Mid-20th Century.

Metropolitan areas including Sydney, Brisbane and Melbourne have undergone substantial coastal expansion since the mid-20th century.

Development has extended across coastal plains previously characterised by vegetation, wetlands and permeable soils. This expansion has fundamentally altered the physical characteristics of these landscapes.

The transformation from natural to built environments has occurred over decades, with coastal settlement intensifying particularly in high-humidity zones where weather extremes interact with dense urban infrastructure.

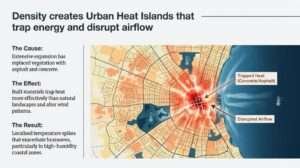

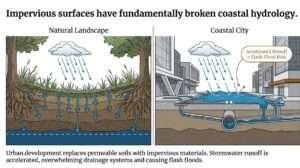

2.2. Urban Heat Islands and Altered Hydrology.

Dense development incorporating asphalt, concrete and other heat-absorbing materials creates urban heat islands.

These areas exhibit a few characteristics, including:

1. They trap heat more effectively than natural landscapes, elevating local temperatures.

2. They alter airflow patterns, disrupting natural cooling mechanisms.

3. They reshape local hydrology by replacing permeable surfaces with impervious materials.

Impervious surfaces accelerate stormwater runoff, increasing flash flood risk during intense precipitation events.

Water that would naturally infiltrate soil now flows rapidly across paved surfaces, overwhelming drainage systems and concentrating flow in ways that amplify flood damage.

2.3. Loss of Natural Buffers.

Coastal development has removed or degraded natural features that previously provided protection such as:

1. Dunes that absorbed wave energy and provided barriers against storm surge.

2. Mangroves that stabilised shorelines and reduced erosion.

3. Floodplains that absorbed excess water during flood events.

4. Wetlands that filtered stormwater and moderated water flow.

The removal of these natural buffers eliminates multiple layers of protection, leaving coastal infrastructure directly exposed to weather extremes without intermediate zones of resilience.

3. The Risk Framework.

3.1. Hazard, Exposure and Vulnerability.

Risk science frameworks typically express risk as the product of three components: Risk = Hazard × Exposure × Vulnerability.

Applied to coastal Australia:

Ø Hazard represents the natural weather events themselves: floods, heatwaves, storms, droughts.

Ø Exposure represents the people, property and infrastructure located in areas affected by these hazards.

Ø Vulnerability represents susceptibility to damage, influenced by factors including infrastructure design, ecosystem health and adaptive capacity.

This framework clarifies that risk does not result from hazards alone.

Even in regions with significant natural climate variability, risk levels depend critically on where and how development occurs.

3.2. Compounding Factors in Coastal Australia.

Australia’s coastal regions exhibit characteristics that amplify risk such as:

1. Extensive coastal urban heat islands increase both exposure and vulnerability.

2. A history of sharp natural climate variability means hazards were already present before recent changes.

3. Continuous coastal settlement expansion raises exposure by placing more people and assets in hazard-prone areas.

4. Degraded coastal ecosystems increase vulnerability by removing natural protective features.

These factors interact multiplicatively rather than additively.

When exposure and vulnerability both increase, total risk rises more rapidly than either factor alone would suggest.

Weather events that might historically have caused limited damage become costly disasters when they impact densely developed areas lacking natural buffers.

4. Constraints on Coastal Adaptation.

4.1. Limited Space for Retrofitting.

Four adaptation strategies are frequently proposed for coastal regions:

1. Installing green infrastructure to absorb stormwater and reduce heat.

2. Replacing impervious surfaces with permeable alternatives.

3. Implementing water-sensitive urban design principles.

4. Restoring coastal ecosystems including dunes, wetlands and mangroves.

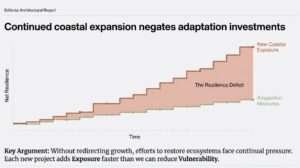

These approaches face a fundamental constraint in many coastal areas: most available land has already been developed.

Decades of coastal expansion have consumed nearly all suitable land, leaving minimal space for large-scale redesign or ecosystem restoration.

Retrofitting existing infrastructure can provide marginal improvements, but cannot fully counteract risks created by the extent and density of coastal development. Interventions are constrained by existing property boundaries, infrastructure networks and built form.

The scale of change required to substantially reduce vulnerability often exceeds what retrofitting can achieve within existing urban footprints.

4.2. The Case for Inland Development.

Given constraints on coastal retrofitting, long-term resilience strategies may require different approaches, such as:

1. Directing future population growth toward inland locations where exposure to coastal hazards is lower.

2. Concentrating economic development in areas where adaptation is more achievable due to greater available space.

3. Limiting or halting further coastal expansion to prevent additional increases in exposure.

Inland areas generally offer:

1. Lower exposure to coastal-specific hazards including storm surge, coastal erosion and sea-level related impacts.

2. Greater availability of undeveloped land for implementing climate-sensitive design from the outset.

3. Reduced pressure on already-stressed coastal ecosystems and infrastructure.

Without redirection of growth inland, efforts to restore coastal ecosystems or stabilise shorelines face continual pressure from ongoing development.

Each new coastal project adds exposure, potentially offsetting gains from adaptation investments elsewhere.

This approach does not eliminate the need for coastal adaptation, but recognises that improving existing coastal areas alone may prove insufficient if development continues increasing exposure faster than adaptation measures can reduce vulnerability.

5. Separating Climate Science from Energy Policy.

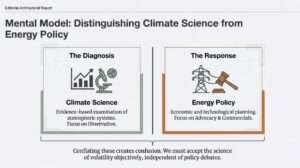

Discussions of coastal weather volatility sometimes conflate climate science with energy policy advocacy, particularly regarding renewable energy technologies.

This conflation can obscure a couple of important distinctions:

1. Climate science examines atmospheric, oceanic and terrestrial systems to understand weather patterns, climate variability and long-term trends. It employs specific methodologies, evidence standards and areas of expertise.

2. Energy policy addresses how societies generate, distribute and consume energy. It involves economic analysis, infrastructure planning, technological assessment and policy design. While climate considerations may inform energy policy, the disciplines remain distinct with separate expert communities and methods.

When organisations or advocates simultaneously promote climate concern and specific energy technologies, questions arise regarding whether messages primarily reflect scientific evidence or commercial or policy interests.

This does not necessarily invalidate either the climate science or the energy proposals, but the combination can make it difficult for non-experts to distinguish scientific findings from advocacy positions.

Effective public understanding benefits from maintaining clear boundaries between:

1. Scientific assessment of climate and weather patterns.

2. Policy discussions about how to respond to those patterns.

3. Commercial interests in particular technologies or approaches.

Each domain has legitimate expertise and evidence, but they address different questions using different methods.

Treating them as a single unified narrative may reduce clarity for audiences seeking to understand either the science or the policy options independently.

6. Conclusion.

Australia’s coastal future depends on understanding the interplay between natural climate variability, urban design, and development choices.

The intensification of ‘climate whiplash’ abrupt shifts between drought, heat, and flooding, exposes how decades of coastal expansion have outpaced natural resilience.

Building a safer, more sustainable Australia requires more than defending existing shoreline developments; it calls for reimagining where and how we grow.

By balancing coastal protection with a deliberate shift toward resilient inland planning, restoring degraded ecosystems, and maintaining clarity between scientific evidence and policy advocacy, we can reduce collective vulnerability.

Australia’s path forward lies in strategies that respect both environmental limits and human safety, ensuring that future generations inherit not just a prosperous nation, but a liveable one.

6.1 Coastal Weather Volatility & Urban Risk Matrix

Risk Component | Definition | Australian Coastal Example | Contributing Physical Mechanisms | Impact of Urban Development | Proposed Adaptation Strategy | Implementation Constraint |

Hazard | Natural weather events such as floods, heatwaves, storms, and droughts. | Rapid swings between drought, extreme heat, and flooding — the signature of climate whiplash. | Warmer air storing more moisture; elevated sea‑surface temperatures energising storms. | Urban heat islands trap heat; natural landscapes replaced with heat‑absorbing materials. | Green infrastructure, permeable surfaces, and restoration of dunes and mangroves. | Coastal land is already heavily built out, limiting space for redesign or ecosystem repair. |

Exposure | People, property, and infrastructure located where hazards occur. | Sydney, Brisbane, and Melbourne expanding across low‑lying coastal plains. | Continuous coastal settlement; intensified development in humid, storm‑prone zones. | Natural buffers replaced with dense infrastructure, increasing exposure to extremes. | Redirect population growth inland; restrict further coastal expansion. | Existing property lines and infrastructure networks make relocation or redesign difficult. |

Vulnerability | Susceptibility to damage shaped by design, ecosystem health, and adaptive capacity. | Removed dunes, drained wetlands, and cleared mangroves along major coastlines. | Destabilised climate patterns interacting with dense, impervious urban surfaces. | Hard surfaces accelerate runoff, overwhelming drainage and amplifying flash‑flood risk. | Water‑sensitive urban design (WSUD) and restoration of wetlands and floodplains. | Retrofitting can only partially reduce risk in already dense, highly modified environments. |

7. Bibliography.

Online Books.

1. Climate Change and Coastal Development in Australia — Nick Harvey

2. Sustainable Coastal Management and Climate Adaptation: Global Lessons from Regional Approaches in Australia — Bruce C. Glavovic and Gavin P. Smith

3. Urban Stormwater Management in Australia — Tim Fletcher and Ana Deletic

4. Planning for Climate Change: Strategies for Mitigation and Adaptation for Spatial Planners — Simin Davoudi, Jenny Crawford, and Abid Mehmood

5. Climate Adaptation Engineering: Risks and Economic Costs — Emiliano Ramieri et al.

6. Coastal Environments and Global Change — Gerd Masselink and Roland Gehrels

7. Resilient Cities: Overcoming Fossil Fuel Dependence — Peter Newman, Timothy Beatley, and Heather Boyer

Online Articles and Reports.

1. State of the Climate 2024 — CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology

2. Coastal Risk Australia: Sea Level, Flooding and Vulnerability Mapping — NGIS Australia

3. Adapting Coastal Cities to a Changing Climate: Policy and Practice in Australia — Barbara Norman (The Conversation)

4. Australian Climate Resilience Framework — Australian Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

5. Urban Heat and Heat Islands: Understanding and Mitigating Extreme Heat in Australian Cities — Parliamentary Library Brief

6. Avoiding Coastal Climate Disasters: Managing Risk in Growing Cities — Nature Climate Change (Nicholls et al.)

7. What Drives Australia’s Extreme Weather? — Bureau of Meteorology

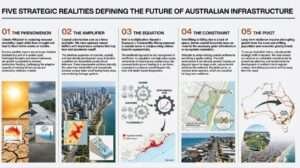

8. Sides (Images)

The below images from my slide deck provide a visual representation of this article.

It shows how Climate Whiplash and urban density necessitate a strategic pivot inland for resilient Australian infrastructure.

1. Climate Whiplash:

a) Rapid shifts from drought to flooding challenge existing infrastructure and community resilience.

b) Extreme weather events are now part of a volatile cycle, with no recovery period between extremes.

c) Three atmospheric drivers: warmer atmosphere, elevated sea surface temperatures, and pattern instability contribute to increased volatility.

2. Urban Density:

a) Coastal urbanization has replaced natural buffers with impervious surfaces, intensifying urban heat islands and increasing runoff.

b) High-density development along coastlines has dismantled crucial natural defences, leading to overwhelmed drainage systems during heavy rains.

3. Risk Management:

a) Risk is a multiplicative factor: Hazard x Exposure x Vulnerability. Rising exposure in coastal zones leads to exponential increases in disaster risk, even with stable hazard frequencies.

b) Traditional risk management approaches are insufficient for current conditions.

4. Retrofitting Challenges:

a) Retrofitting existing coastal settlements is failing due to lack of space for green infrastructure and ecosystem restoration.

b) Dense urban footprints limit the implementation of nature-based solutions essential for long-term resilience.

5. Strategic Pivot:

a) A fundamental shift is required to decouple growth from vulnerable coastal zones and incentivize development of resilient inland centres.

b) Inland development offers advantages such as lower hazard exposure, reduced ecosystem pressure, and available land for climate-sensitive design.