Earth Like A Kid With An Ant Farm

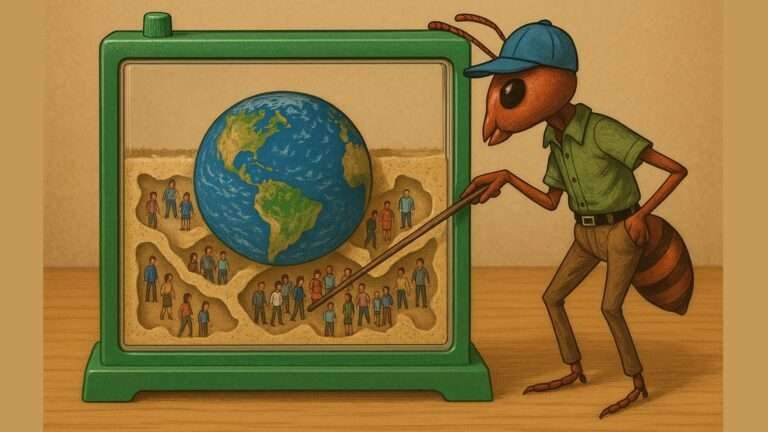

Humanity's Treatment Of Earth Is Like A Kid With An Ant Farm.

In the satirical piece below in section 1.0, a conservationist recently poked fun at humanity’s tendency to treat Earth as an ant farm, suggesting that our planet was nothing more than a playground for our ambitions and fun, from overhunting to overfishing to altering ecosystems for short-term gains.

This 283-word piece of humor is laced with irony and underscores a serious truth: humans have often acted without fully considering the consequences for the planet.

This page dives into that critique, offering a comprehensive examination of ways that humans have harmed the environment, including both well-known issues and emerging concerns like the clearing of forests for renewable energy projects.

By examining these actions, I aim to highlight where we’ve been less than clever and propose a path toward more balanced, intelligent stewardship of Earth.

1.0 Humanity Is Like A Kid With An Ant Farm.

Earth has served several functions for mankind; it has entertained us while also serving an instructional function. The huge amount of work we’ve expended over the years messing with this planet has really improved our cognitive behavior and spurred our creativity.

Although our activities to modify the planet have occasionally backfired on us, the Earth experiment has been a success in terms of developing our physical and mental talents, which will be extremely useful when we go on to the next one. We now have some fantastic stories to tell other species when we become interplanetary.

Another way Earth has been beneficial to humans is that it has satisfied our predatory instincts. The advancement of firearms, hunting equipment, and maritime research vessels has enabled humans to demonstrate our natural hunting abilities. Nothing beats chasing a weaker species halfway across a planet to get in some much-needed exercise and avoid boredom.

Importantly, actions aimed at modifying this planet deepen our bonds with one another; each time we come up with a new idea, teams are established, as are long-lasting relationships and happy memories.

It’s possible that some alien species who don’t know us well may look at what we’ve done and wonder, “How could such a cute, cuddly race like humans be so viciously nasty to a planet and all other life forms?” But, as we all know, “haters are gonna hate.”

Sure, we may appear charming, cuddly, and innocent to some creature spying on our planet from hundreds of light-years away, but they must spend time getting to know us before passing judgment. We cannot reject our predatory tendencies in order to appease the consciences of all other creatures in the universe.

2.0 Earth as an Ant Farm: The Uncomfortable Truth Behind the Satire.

The sardonic piece above, while amusing, reflects a disturbing reality about humanity’s relationship with Earth. In the 1950s, a simple toy called the ant farm captured the imagination of children worldwide.

These transparent containers, popularized by Uncle Milton’s Ant Farm, allowed kids to scoop up ants from their natural habitats and watch them build tunnels, forage, and live in a controlled environment.

For many, it was a source of wonder and entertainment, a chance to poke, prod, and experiment with a miniature world.

As we reflect on those childhood ant farms, a striking parallel emerges: the way humans have treated Earth mirrors how children once treated their ant colonies.

Just as ants were confined and manipulated for amusement, we’ve reshaped the planet’s ecosystems for our own purposes, often with little regard for the consequences. This page explores this analogy, drawing connections between ant farms and human environmental impact, and considers what it teaches us about our role as stewards of Earth.

3.0 The Ant Farm: A Microcosm of Control.

Ant farms, first conceptualized by French entomologist Charles Janet in 1900 and later commercialized by Frank Eugene Austin in the late 1920s, became a cultural phenomenon in the 1950s through Uncle Milton’s Ant Farm.

Children would collect ants, typically harvester ants, chosen for their size and activity and place them in clear plastic or glass containers filled with sand or gel.

Inside, the ants would build tunnels, carry food, and care for their young, all under the watchful eyes of their young captors.

This setup gave children a sense of complete control over a living system. The ants, removed from their natural environment, were confined to a space designed for human observation and amusement.

Their behaviors were fundamentally altered by the artificial conditions, and their survival depended entirely on the care (or lack thereof) provided by their keepers.

Kids could observe the ants’ complex social structures, but they also had the power to manipulate the colony, adding different foods, shaking the farm, or introducing obstacles to see how the ants would react.

This dynamic bears a striking resemblance to how humans have interacted with Earth’s ecosystems, reshaping landscapes and exploiting resources to suit our immediate needs and desires.

4.0 Parallels with Human Treatment of Earth.

Just as ants in a farm are confined to a human-designed environment, humans have systematically imposed their will on the planet, altering vast areas for agriculture, urbanization, and resource extraction. The parallels are both numerous and troubling.

Consider deforestation: in regions like the Amazon, forests are cleared for farming or logging, displacing countless species and disrupting ecosystems that have evolved over millennia, much like ants are displaced from their natural colonies and forced into artificial habitats.

Urban sprawl fragments remaining natural habitats, isolating wildlife in ever-shrinking patches of land, creating the terrestrial equivalent of an ant farm’s confined space.

Mining operations (although mostly essential) extract resources but leave behind scarred landscapes and sometimes contaminated water systems, mirroring the way captive ants are subjected to artificial conditions that severely limit their natural behaviors and life cycles.

The tongue-in-cheek commentary in section 1 highlights this parallel with uncomfortable accuracy.

Even well-intentioned projects can fall into this pattern. The clearing of native forests and bushlands for large-scale solar and wind farms, while intended to combat climate change, often destroys habitats critical for native flora and fauna.

The proposed Wooroora Station Wind Farm in North Queensland, which was thankfully rejected, would have cleared over 500 hectares of native vegetation, threatening various species.

This scenario is disturbingly reminiscent of a child rearranging an ant farm’s layout for their own purposes, unaware or unconcerned about the devastating impact on the ants’ well-being.

As I often emphasize, simply putting the word ‘renewables’ in a sentence doesn’t grant us carte blanche to do whatever we want to this planet.

Aspect | Ant Farm | Human Treatment of Earth |

Confinement | Ants removed from natural habitat, placed in controlled artificial environment | Ecosystems altered or destroyed for human purposes, species confined to fragmented habitats |

Manipulation | Children poke, prod, add elements to observe reactions, altering ant behavior | Humans experiment with ecosystems through species introduction, chemical use, often with unintended consequences |

Purpose | Primarily entertainment and education, little regard for ants’ natural roles | Often economic or societal gain, prioritizing human needs over environmental health |

Consequences | Colony stress, behavioral changes, potential collapse from unnatural conditions | Biodiversity loss, climate change, ecosystem degradation, mass extinctions |

In both cases, the controlling force, whether a curious child or ambitious humanity, consistently prioritizes its immediate goals over the long-term needs and health of the living systems it manipulates.

5.0 Experimentation and Unintended Consequences.

Children with ant farms often experiment out of curiosity, adding unusual foods, flooding the enclosure, or introducing foreign objects to observe how the ants respond. These actions, while potentially educational, frequently disrupt the colony’s delicate balance, sometimes leading to stress, behavioral changes, or complete collapse.

Similarly, humans have conducted countless large-scale experiments on Earth’s ecosystems, often with devastating and unforeseen impacts.

The introduction of non-native species provides perhaps the most stark example of such experimental folly.

In Australia, European rabbits introduced in 1859 became one of the most destructive invasive species in history, devastating native vegetation and outcompeting indigenous wildlife across vast areas of the continent.

In the United States, kudzu vine, originally planted in the 1930s to control soil erosion, has since smothered millions of acres of native plants, earning the ominous nickname “the vine that ate the South.”

Agricultural practices have yielded similar unintended consequences. The widespread use of pesticides and fertilizers has dramatically boosted crop yields, but has also caused extensive water pollution, creating massive dead zones in bodies of water like the Gulf of Mexico, where oxygen levels have dropped too low to support marine life.

Even well-intentioned infrastructure projects, such as large dams built for hydroelectric power generation, have disrupted entire river ecosystems and displaced both wildlife and human communities, much like a child’s “improvement” to an ant farm might inadvertently destroy the colony’s carefully constructed social structure.

These parallels illuminate a shared human tendency to act without fully understanding or considering the long-term consequences of our interventions.

Just as a child’s curiosity and desire to “improve” their ant farm can lead to ecological chaos within that miniature world, human ambition and innovation have repeatedly triggered ecological imbalances and disasters on a global scale.

6.0 Ethical Reflections: Who Gave Us the Right?

The ant farm analogy raises profound ethical questions that strike at the heart of humanity’s relationship with the natural world.

Is it morally acceptable to confine ants for our amusement and education, knowing they’re being removed from their natural roles and environments?

I’m not trying to get Ant Farms banned ok, I’m just highlighting that what Alien race came to this planet and appointed humans the boss?

Sure, most would argue that ant farms foster appreciation for nature and biology, teaching children about complex social behaviors and ecological relationships and that’s ok, I’m merely just trying to illustrate a much larger point.

Maybe there will be people out there that view them as a form of unjustifiable captivity, depriving sentient creatures of their freedom and natural environment for purely human-centered purposes. They might say, how would we like it if the situation was reversed?

These same ethical debates apply to human activities on Earth, but with vastly higher stakes. The ongoing biodiversity crisis, with approximately one million species currently at risk of extinction due to habitat destruction, climate change, and pollution, underscores the urgency of these concerns.

The section 1.0 hard biting satire reflects a deep frustration with the mindset that positions humans as the ultimate authority over nature, free to exploit and manipulate it however we see fit.

This mirrors the casual way a child might view an ant farm as merely a toy, completely disregarding the intrinsic value and complex needs of the creatures within. By drawing this uncomfortable parallel, we’re compelled to question whether our actions on Earth are truly sustainable and just, and whether we’ve been treating our planet as a disposable resource rather than recognizing it as a shared home that deserves our respect and careful stewardship.

The question does remain, “Who gave us the right to treat Earth as our personal laboratory, and at what point does human ingenuity cross the line into destructive arrogance?”

7.0 Learning from the Ant Farm: A Path Forward.

The ant farm analogy, while simple, offers valuable insights into our relationship with the natural world. Just as children can learn from observing the effects of their actions on ant colonies, we can learn from honestly assessing the environmental consequences of our collective behavior.

The fragility of an ant colony mirrors the fragility of Earth’s interconnected ecosystems, where seemingly small changes can trigger cascading effects across entire food webs and climate systems.

By recognizing these parallels, we can begin to develop more mindful approaches to planetary stewardship. For instance, in renewable energy development, we can prioritize degraded or already cleared lands for solar and wind installations, minimizing additional habitat loss.

Australia’s impressive 3.7 million rooftop solar installations demonstrate the potential to dramatically reduce our reliance on large-scale land clearing for energy production, though achieving complete energy independence through distributed generation remains challenging due to grid stability requirements and variable energy demands.

Globally, we can implement more sustainable practices across multiple sectors: precision agriculture that minimizes chemical inputs and soil degradation, widespread adoption of truly biodegradable materials, and significantly stronger conservation policies that protect critical habitats before they’re destroyed.

Engaging local communities, including Traditional Owners and indigenous peoples worldwide, ensures that development projects respect both ecological integrity and cultural values that have sustained human-environment relationships for millennia.

The transition from destructive to regenerative practices requires acknowledging that human intelligence includes the wisdom to recognize our limitations and the humility to work with natural systems rather than against them.

8.0 Human Ingenuity or Folly?

Let’s take a comprehensive look at our environmental impacts, all in the name of humans getting whatever they want, no matter the harm it might cause.

The below table examines human activities that have in some way harmed Earth’s ecosystems, reflecting the reckless behavior critiqued in section 1.0

These impacts range from direct actions like poaching to systemic issues like industrial pollution, each contributing to biodiversity loss, climate change, and ecosystem degradation on scales that would have been unimaginable to previous generations.

Human Activity | Type of Harm | Details and Examples |

Industrial pollution | Contaminates air, water, and soil | Factory emissions have created widespread contamination. While improvements have been made, significant challenges remain |

Plastic pollution | Harms marine life, pollutes ecosystems | Approximately 14 million tons of plastic enter oceans annually, ingested by marine animals and entering food chains |

Introduction of invasive species | Disrupts native ecosystems | Historical decisions to introduce non-native species have caused extinctions, often without understanding long-term consequences |

Overpopulation and urbanization | Destroys biodiversity, strains resources | Growing populations drive deforestation and resource depletion. Urban sprawl fragments ecosystems and destroys pristine habitats |

Transportation emissions | Contributes to air pollution, climate change | Vehicle emissions worsen air quality and accelerate climate change. Transition to cleaner fuels and electric options remains incomplete |

Waste management failures | Pollutes land and water | Poorly managed landfills and incineration release toxins. Leachate from electronic waste poisons water tables |

Water over-extraction | Depletes water resources, disrupts ecosystems | Groundwater overuse reduces river flows, harming aquatic life. Need for water recycling and zero-discharge desalination |

Agricultural chemical pollution | Contaminates water, harms aquatic life | Pesticide and fertilizer runoff causes algal blooms and ocean dead zones |

Light and noise pollution | Disrupts wildlife and human health | Artificial light affects nocturnal animals; noise pollution disturbs marine species and migration patterns |

Oil spills and leaks | Devastates marine environments | Drilling and shipping accidents kill marine life. Need for zero-risk extraction and transport methods |

Destructive mining practices | Destroys landscapes, pollutes waterways | Mountaintop removal and poorly located mines devastate forests and contaminate water systems |

Deep-sea mining | Disrupts fragile ocean ecosystems | Mineral extraction threatens long-term damage to poorly understood deep-sea habitats |

Fishing industry damage | Reduces biodiversity, destroys habitats | Bycatch kills non-target species; bottom trawling destroys seafloor ecosystems; ghost fishing gear continues killing |

Poaching and illegal wildlife trade | Drives species extinction | Illegal hunting for body parts threatens endangered species, highlighting concerning gaps in human reasoning |

Recreational hunting | Reduces biodiversity | Perhaps humans could find alternative recreational activities that don’t involve killing other species |

Eutrophication | Causes algal blooms, dead zones | Agricultural runoff creates oxygen-depleted zones in water bodies |

Desertification | Converts fertile land to desert | Poor historical land management has created extensive arid regions through soil degradation |

Fast fashion | Contributes to waste and pollution | Generates approximately 2.1 billion tons of textile waste annually, polluting water systems |

Overfishing | Disrupts ocean food chains | Fishing down the food web shifts marine ecosystems, with some predictions of collapse by mid-century |

Mass extinction acceleration | Drives species loss | Human activities are driving the Sixth Mass Extinction, with 69% wildlife population decline since 1970 |

Coral reef destruction | Threatens marine ecosystems | Ocean warming and pollution causing widespread reef death and ecosystem collapse |

Nitrogen cycle disruption | Causes eutrophication, emissions | Excess nitrogen from fertilizers contributes to both water pollution and greenhouse gas emissions |

Microplastic pollution | Pollutes oceans, enters food chains | Textile washing contributes 35% of ocean microplastics, affecting marine life and human health |

Space debris creation | Threatens orbital safety | Over 27,000 pieces of debris orbit Earth, risking collisions and limiting future space access |

Urban heat island effects | Increases temperatures, energy demand | Concrete-heavy cities raise local temperatures, exacerbating heat waves and increasing energy consumption |

Agricultural antibiotic overuse | Creates health risks | Livestock antibiotic overuse fosters antibiotic-resistant bacteria, threatening human health |

Renewable energy land clearing | Destroys native habitats | Large-scale solar and wind projects clearing forests demonstrate how good intentions can have harmful consequences |

9.0 A More Balanced Approach to Renewable Energy Development.

The clearing of native forests and bushlands for solar and wind farms represents a prime example of well-intentioned actions producing unintended environmental consequences.

These projects should never receive approval if they require clearing hundreds or thousands of hectares of native vegetation, impacting numerous species of flora and fauna.

While renewable energy projects aim to reduce carbon emissions and combat climate change, they can simultaneously harm the very ecosystems we’re trying to protect.

A more intelligent approach would maximize rooftop solar installations, every home and building should have its roof covered with solar panels.

This distributed approach could significantly reduce the need for habitat-destroying utility-scale projects, though it may not fully meet all energy demands due to grid stability requirements and storage limitations.

We must also remember that renewable energy encompasses far more options than just wind and solar. Geothermal, tidal, wave, waste to energy, sewage to energy and hydroelectric projects can provide clean energy with different environmental footprints.

The key is matching energy solutions to landscapes in ways that minimize ecological disruption while maximizing clean energy production.

10.0 Learning from Our Mistakes: The Path to Planetary Stewardship.

The list of environmental impacts detailed above highlights humanity’s remarkable capacity for both brilliant ingenuity and devastating folly.

Many of these problems stem from a persistent lack of foresight, an overemphasis on short-term benefits, and a failure to recognize the interconnected nature of Earth’s systems.

However, we possess the tools necessary to mitigate these impacts through rigorous science, thoughtful policy development, and coordinated collective action. The challenge lies not in our technical capabilities, but in our willingness to prioritize long-term sustainability over immediate gratification.

What’s the point of having certain net zero targets if we currently cannot achieve them without doing more harm than good?

Engaging communities worldwide, including Traditional Owners and indigenous peoples whose cultures have successfully maintained sustainable relationships with their environments for thousands of years, provides crucial guidance for development approaches that respect both ecological integrity and cultural values.

Integrating true environmental costs into policy decisions and business models can help align human economic progress with planetary health rather than treating them as competing interests.

The transition from destructive exploitation to regenerative stewardship requires acknowledging that true human intelligence includes the wisdom to recognize our limitations, the humility to learn from our mistakes, and the courage to fundamentally change course when our current path leads toward destruction.

11.0 Conclusion: From Ant Farm to Stewardship.

Humans have reshaped Earth in profound and often irreversible ways, typically with a troubling combination of remarkable ingenuity and reckless shortsightedness. From overhunting species to extinction to clearing ancient forests for renewable energy projects, our actions have consistently prioritized immediate gains over long-term sustainability and the intrinsic value of other species.

The satirical critique in section 1.0 that inspired this page serves as more than entertainment, it’s a mirror reflecting our collective behavior back to us in ways that should make us deeply uncomfortable.

When viewed from the perspective of other species, or hypothetical alien observers, human treatment of Earth does indeed resemble a child carelessly experimenting with an ant farm, poking and prodding without fully understanding or caring about the consequences.

Yet this recognition need not lead to despair. By honestly acknowledging our mistakes and leveraging advances in technology, policy, and ecological understanding, we can chart a fundamentally different course.

The choice before us is clear: continue treating Earth as our personal laboratory and playground, or evolve into genuine stewards who recognize that our long-term survival and wellbeing are inseparable from the health of the planet we share with millions of other species. The ant farm analogy ultimately asks us to grow up, to move beyond the destructive curiosity of children and embrace the responsible wisdom that our intelligence and technological capabilities demand. The planet’s future, and our own, depends on making that transition before it’s too late.